1.

The experience of fright appears (when we philosophise) to be an amorphous experience behind the experience of starting. |

All I want to say is that it is

misleading to say that the word

“fright” signifies something which goes

along with the experience of expressing fright. |

There is here again the queer case of

a difference between

what we say, when we actually

try to see what happens, & what

we say when we think about it

(giving over the reins to

language). |

The ‘far away’ look, the dreamy voice

seem to be only means for conveying

the real inner feeling. |

“Therefore there must be something

else” means nothing unless it expresses

a resolution to use a certain

mode of expression. |

Suppose you tried to separate the feeling

which music

gives you from hearing music. 2. |

Say & mean “long, long

ago–”, “lang

ist es her–”& now put instead

of these words new ones with many

more syllables & try if you can

put the same meaning into the words.

Put instead of the copula a very

long word say “Kalamazoo”. |

Puella, Poeta

“‘masculine’ &

‘feminine’ feeling”

of || ‘attached’

to a. |

Aren't there two (or more) ways to

any event I might describe? |

We say “making this gesture isn't

all”.

The first answer is: We are talking about

the experience of making

the || this

gesture.

Secondly: it is true that different

experiences can be described by

the same gesture; but not in the

sense that one is the pure one

& the others consist …. |

Wie ist es wenn man einmal die

besondere Klangfarbe eines Tones

merkt || hört ein andermal nur den Klang als

solchen?

3. |

◇◇◇◇◇◇

“Ich nenne diesen Eindruck ‘blau’”. |

Wie kann man denn die genaue Erfahrung in

‘Poeta’ etc.

beschreiben? |

The philosophical problem is:

“What is it that

puzzles me

about || in this matter?” |

To give names is to label things;

but how does one label impressions. |

Das männliche a & das weibliche a. |

Es läßt sich über die besondere || bestimmte Erfahrung einiges sagen & außerdem

scheint es etwas, & zwar das

Wesentlichste, zu geben was sich nicht beschreiben

läßt. |

Man sagt hier, daß ein bestimmter

Eindruck benannt wird.

Und darin liegt etwas Seltsames &

Problematisches.

Denn es ist als wäre der Eindruck

4

etwas zu Ätherisches um ihn zu benennen.

(Den Reichtum einer Frau heiraten.) |

Du sagst Du hast einen ungreifbaren Eindruck.

Ich bezweifle nicht, was Du sagst aber ich

frage ob Du damit etwas gesagt hast.

D.h. wozu hast Du diese Worte geäußert, in welchem

Spiel. |

It is as though, if || although you can't tell me

exactly what happens inside you, you can nevertheless tell me something

general about it.

By saying e.g. that you are having an

impression which can't be further described. |

As it were: There is something further about it,

only you can't say it; you can only make the

general statement.

It is this idea || form of expression which plays hell with us. |

“There is not only the gesture but a

particular feeling which I can't describe”: instead

of that you might have said: “I am

trying to point out a feeling to you”

which || this would be a grammatical remark showing

how my information is meant to be used.

This is almost similar as though I said “This I call

‘A’ & I am pointing out a

colour to you not a

shape”. |

How can we point to the colour & not to the shape?

Or to the feeling of toothache & not to the tooth

etc.? |

What does one call “describing a feeling to

someone”? |

“Never mind the shape, – look at the

colour!” |

“Was there a feeling of pastness when you said you remembered

…?”

‘I know of none’. |

How does one point to a number, draw attention to a number, mean

a number? |

How do I call a taste

“lemon-taste”?

6

Is it by having that taste & saying the words: “I

call the taste …”? |

And can I give a name to any one

taste-experience without giving the

taste a common name which is to be used in common language? –

“I give my feeling a name, nobody else can know what the

name means.” |

A slave has to remind me of something

& isn't to know what he reminds me of. |

7 |

“I use the name for the impression

directly & not in such a way that anyone

else can understand it.” |

Buying something from oneself.

Going through the operations of buying. |

My right hand selling to my left hand. |

Gefühls- (Gedanken-) Übertragung. |

Eine gute Art eine Farbe zu benennen wäre, in einer

entsprechend gefärbten Tinte den Namen schreiben. |

“I name the feeling”– I

don't quite know how you do this, what use you are

making of the word || name. |

“I'm giving the feeling, which I

have || I'm having just now a

name”. –

I don't quite know what you are doing. |

One might say: “What is the use of talking of our

feeling at all.

Let

8 us devise a language which really

only says what can be understood.”

Thus I am not to say “I have a feeling of

pastness”: But |

“This pain I call ‘toothache’ & I can

never make him understand what it means”. |

We are under the impression that we can point to the pain, as it were

unseen by the other person, & name it. |

For what does it mean that this pain || feeling is the

meaning of this name? |

Or, that the pain is the bearer of the name?

It is the substantive ‘pain’ which puzzles us. This substantive seems to produce an illusion. What would things look like if we expressed pains by moaning & holding the painful spot? Or that we utter the word pain pointing to a spot. “But that the point is that we should 9 say ‘pain’ when there

really is pain.”

But how am I to know if there really is pain? if what I feel really is pain? Or, if I really have a feeling?‒ ‒ ‒ |

Es ist sehr nützlich zu bedenken: Wie würde ich in einer

Gebärdensprache ausdrücken: “ich hatte keine Schmerzen, aber

stellte mich, als ob ich welche hatte”? |

“He has pains, says he has pains & saying

‘pains’ he means his pains.”

How does he mean his pains by the word ‘pain’

or ‘toothache’? |

“He says ‘I see green’

& means the colour he sees.” –

If asked afterwards what did you mean by ‘green’ he

might answer ‘I meant the colour’, pointing to it.

10 |

“In my own case I know that when I say ‘I

have pain’ this utterance is accompanied by something;– but is it also accompanied by something in another man?”

In as much as his utterance needn't be accompanied by my pain. I may say that it isn't accompanied by anything. |

“I know what I mean by ‘toothache’ but

the other person can't know it.” |

Als negation: “The deuce he

is ….” |

Die Philosophie eines Stammes der als Negation nur den

Ausdruck benützt || kennt:

“I'll be damned

if …”. |

On a beau

dire …. |

“Man kann nie einen ganzen Körper sehen sondern nur

immer einen Teil seiner Oberfläche.” |

“Give the impression a name!”

that seems to have sense. “It seems to me that I can mean the impression”. It seems to me that I can will the table to approach. “Can one push air?” 3. |

We said that what we described as “numeral

equality”, “being 1-1 correlated”,

“having the number n” were widely differing

phenomena.

That therefore it was an illusion to think that to say

“the classes fall in pairs” is, generally speaking an

analysis of what we call numeric equality in simpler terms.

We can if we like put “being numerically equal” =

“falling into pairs” but the use of the one

expression just as of the other has got to be explained in the particular

case.

This we only forget.

Thinking about a very special class of examples.

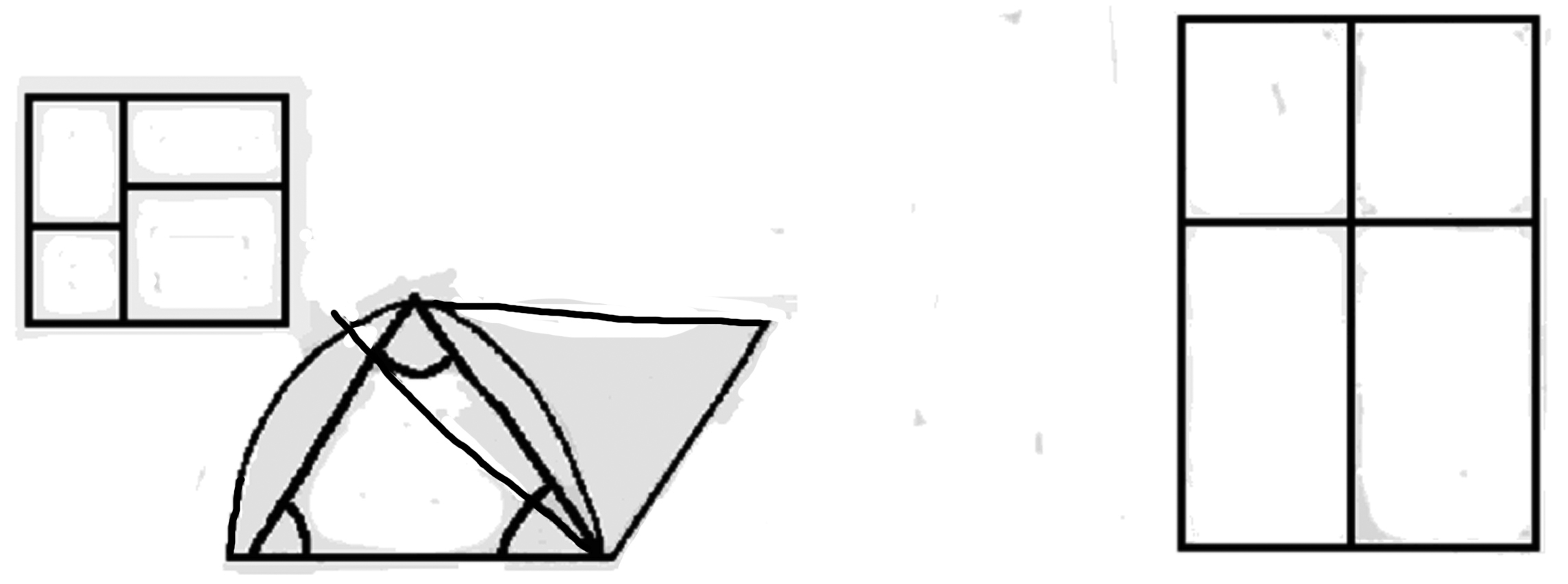

One could also say that a length a was twice another one b if two a superimposed gave b. Application for wavelengths. This brings me to the topic of 8 demonstration.

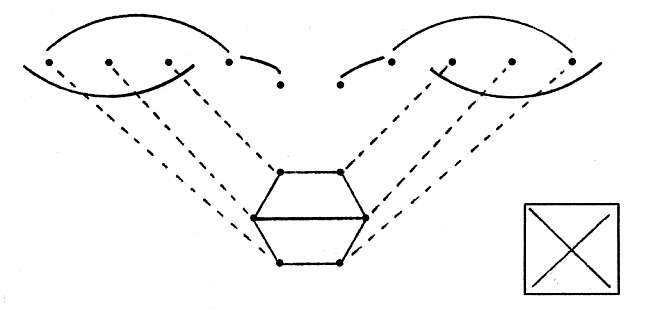

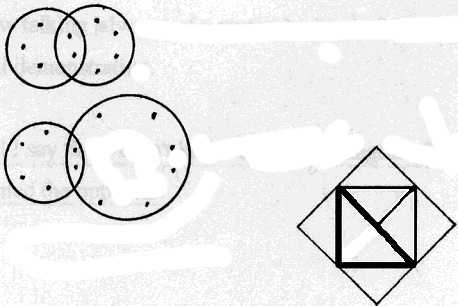

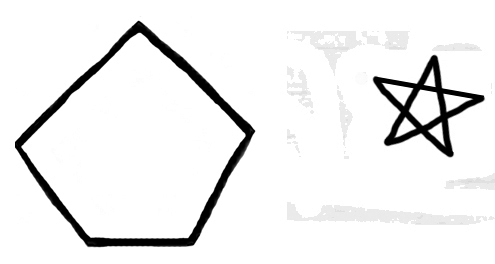

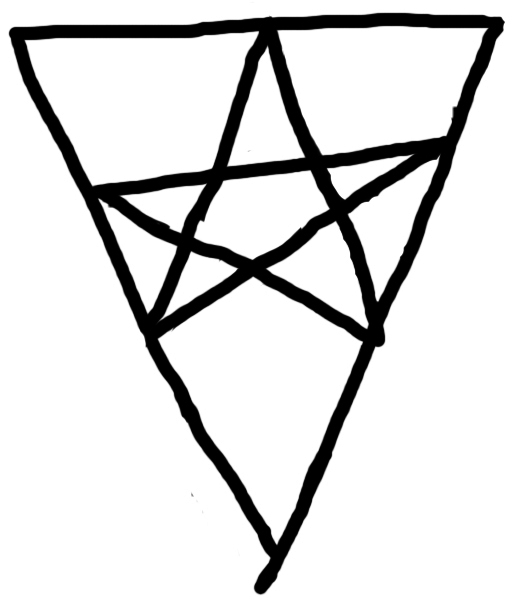

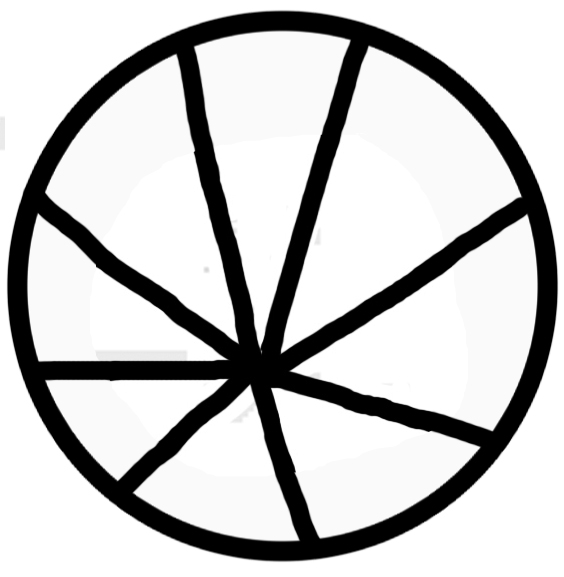

1)  number of outer

vertices =

5.

number of outer

vertices =

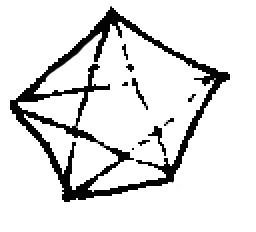

5.Compare with “the Hand has 5 Fingers.” Timelessness. The same holds of “The number of outer vertices = number of inner vertices”. Question which is answered by this proposition timeless. Apparent generality of demonstration The copula has no tenses. ◇◇◇ idea is that the idea of a pentagram is bound up with a cardinal number Now, we could make all sorts of connections. “It is the essence of these figures to be capable of being divided || connected in this way”. 9 |

Pythagoras Is the result of the process taken as a standard or not.  “These two

triangles by this nature give the

rectangle”. “These two

triangles by this nature give the

rectangle”.4 This aspect might never have struck you.

10

a

+ (◇◇◇) = (◇◇◇ + b) + c

It seems you can't get out.

You must adopt a + (b + c) =

(a + b) + c if you adopt

a + (b + 1) = (a + b)

+ 1. a + (b + 1) = (a + b) + 1 a + (b + 2) = (a + b) + 2 |

But need we really say that a + (b + 2) =

(a + b) + 2 follows from

a + (b + 1) =

(a + b) + 1? |

The reasoning is:

a + (b + 2) = a + (b + (1 + 1)) = a + ((b + 1) + 1) = = (a + (b + 1)) + 1 = ((a + b) + 1) + 1 = (a + b) + (1 + 1) 5 + (6 + 1) = (5 + 6) + 1 5 + (6 + 2) = |

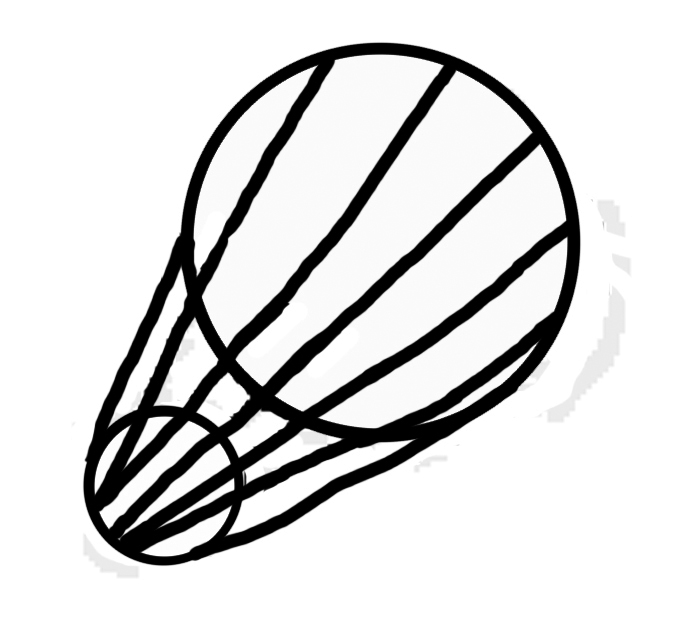

I show you a curve drawn in a pentagon which you had never

thought of & I say: I am showing you that

11. this curve can be

drawn, – or: that there is such a curve in the pentagon.

That there are two twos in four. |

Is there really no way out of saying, say, that a triangle which has

3 equal sides has also three equal angles. |

Does  consist of consist of

& &

?

It depends what kind of dispute it is.

You could say it consisted of ?

It depends what kind of dispute it is.

You could say it consisted of Counting5 12

This

doesn't show that a + b fits butit shows that it looks like it does. “What kind of figure do you get if you draw the diagonals in a Pentagon?” What sort of body do you get if you draw the diagonals on a dodecaeder. What kind of number do you get if you draw 3s in 9. What kind of colour do you get if you mix red with yellow? “The figure shows him that a pentagram fits into a pentagon”. Is this an experimental result? 13. |

I am now talking always of a particular kind of

demonstration; what one might call a visual demonstration.

|

In what sense could I say that I didn't know that the

pentagram fitted the pentagon?

Could I have imagined the opposite?

Suppose I had imagined the opposite in some sense then in the same sense I could still hold the opposite after the demonstration. |

“I never knew that I could see the Pentagon

& its diagonals in this aspect.” 7 “Oh, that's how it fits!” Two tunes fitting together. 15 |

8 “I don't know whether the pentagram fits the pentagon. If so the diagonals of a pentagon must give a pentagram. Let's try it.” Is to see the figure  an experiment?

Or to see side by side the figures an experiment?

Or to see side by side the figures ? ?

But doesn't it teach us something? “It never struck me.” |

It seems we are learning by experience a timeless truth about the shape of

a Pentagon & of a Pentagram. |

“I never knew that one could look at it

16 that way.

I had never seen the pentagram in the pentagon.”

|

It is a new experience to me.

But is it the experience teaching me that the pentagram fits the

pentagon? |

“The visual image p fits

the visual image P.”

The importance of this proposition lies in this that

it seems a proposition of experience &

that on the other hand it also is used as a

proposition of geometry

i.e. of grammar. |

Problem: “Draw that Star which will fit the

Pentagon.”

This is a mathematical problem. |

“What do the diagonals of a P look

like?” |

We look at a puzzle picture & find a man in the foliage of a

tree.

Our visual impression changes.

But can't || mustn't we say that the new

experience would have been impossible if the old one

hadn't been what it was?

Such that we seem bound to say the new

experience was already preformed in the old

one.

Or that I found something new which was already in the essence of the

first picture. |

We seem to have demonstrated an internal property of the old

picture.

18 |

Die mathematische Frage. Could the Pythagorean theorem be assumed instead of being deduced? |

To see five figures as 3

figures + 2 figures.

If 5 is =

2 + 3 it

can't mean anything to see 5 as

2 +

3.

You could divide 5 into 2 + 3 but not into 3 + 3 as you could 6.

20

|

The whole question is really: “can it strike you

what a thing is?” 10 It seems you can find out something about the nature of a thing by experience. About its internal nature. Thus e.g. a similarity can strike you; the fact that a complex contains a constituent; even 21 identity of shape.

Two tunes fitting. |

“One can see immediately that 4 consists of

2 +

2”.

This is nonsense if 4 = 2

+ 2. |

~ [~p ∙ ~(~r ∙ ~s)] ∙ ~[~(~t ∙ ~~s ∙ ~t)) ∙ ~p] |

What do I do when I draw your attention to a fact about,

say, this formula?

It seems I make you see something about its essence.

You get a new experience; but this experience, ¤ it seems, teaches you

something about the essence the internal nature of the formula.

It seems to teach you a mathematical (or logical) truth

& this does not seem to be a rule of grammar but a truth about the

22

nature of things. |

If I made an experiment with a certain figure we can ◇◇◇

imagine this or that result.

But if I draw your attention to a feature … |

It consists of … appears to have 1) a grammatical meaning 2)

a physical meaning & 3) a meaning lying between these

two. |

We seem to learn something about the very

sense-datum. |

A certain symbolism will easily go with a certain aspect of looking at a

thing. |

“They regard the square as a double right

angle.” |

One couldn't call 0˙3̇

a shorthand for

0˙333 ….

Except insofar as 0˙33 … is also a shorthand for

0˙333 …. |

“Don't try to find a 4 in the development

it's hopeless!” –

“Don't multiply

25 × 25

24 again & again in the hope to find

600; it's hopeless!”

What's it like to try to find a 4 in the development of 1 : 3? And what is it like to find a 4. |

What is the importance ¤ of

the question: “What is it like?” or

“What is the verification?” |

Kein Kalkül ist im “Widerspruch mit der Logik”

d.h. mit gewissen Regeln die über allen andern

stehen.

Die Annahme einer obersten Logik ist es, die hier irreführt. |

What we should call finding a 4 in 1/3

obviously depends upon the operations in this case. |

What does it mean to imagine getting a result from a

calculation?

How far is this imagination to go? |

“There isn't a 4 in the first million

places”– “You've got a quick way of

calculating that!” |

Imagine this operation: A decimal

25 fraction constructed by multiplying again

& again 25 ×

25: 0˙625625625 … Look for an 8 in it!” “You know that you will never find an 8” means: “Don't try to divide 2476 without remainder by 3 it's hopeless”. |

In which case is it hopeless to find a particular result by a

calculation? |

Calculating is the process of imagining a calculation. |

“I can hope to find an 8 in the Product

284 × 379.” |

To say “it's hopeless to find a certain result

really means: our calculation has already shown it to

be wrong. |

Or: we have a calculation which we make have that

opposite result. |

What is the 65th || 56th

place of 1 : 7?

You can now say it seems what the 10¹⁰ place

‘will’ be. 26 |

How can one calculation anticipate the result of another? |

Or: Our

calculus || calculation

has already decided against it. |

What does it mean: to prophesy what one will correctly

find. |

|

Das Bild “Alle” angewandt auf die Unendlichkeit. |

To show mathematically that a 4 can be found is to describe what it is

like to find a 4.

And to find a 4 is here a process in space and time. |

“Find, as the result of a calculation” &

“Find, otherwise”. |

In 1 : 7 gibt es ein endliches

Problem & ein unendliches.

27 |

❘ ❘ ❘ ❘ ❘ ❘ ❘ ❘ ❘ ❘ ❘ ❘ ❘ 13 : 5 = 2 311 Two processes of calculation lead to the same result. |

“What if they at some stage did not lead to the same result”. – “That is impossible, we couldn't imagine their not leading to the same result.” But then the proof of their leading to the same result showed us what it was like to lead to the same result. |

The difficulty consists in this that it here seems impossible to

imagine anything but what really is the case: And

that of course means nothing!

We don't seem to be able to imagine finding a 4, because there is a three there. But then how are we capable of imagining to find a 3 as there is a 3 there? |

If I say I can't imagine a 4

29 to result it means that the calculation

shows me what it means to imagine a 3 to result & gives no sense

to the proposition “I imagine a 4 to

result”. |

x² +

ax + b = 0

“Solve this equation algebraically!”

|

“Do something that has an analogy to

….”

But we can't be sure that we shall not in the end give up the idea of something being analogous to …. |

The existence of a || something we call

the ‘solution’ seems to show clearly that there

was a clear & definite problem. |

Suppose we said that a solution is a solution only

so far as it could have been described

before it was found. |

“Solve x² + 2ab + b² = 0.” “Solve x² + 4x + 5 = 0.” 30 |

“We can't imagine that 1 : 7

should not repeat itself after the dividend has come

back.”

|

We have two ways of calculating the

10¹⁰th

place & we can't imagine that they lead to different

results. |

Ist es eine Bestätigung hierfür wenn die beiden

Bemerkungen in einem bestimmten Fall übereinstimmen?

|

Is it different to say “they lead to the same

result” & “they must lead

to the same result”? |

Does it mean anything to “prophesy” the result of a

calculation? |

We say we can't imagine that the two processes should not

lead to the same result.

What does it mean, we can't imagine it? 31 |

Must we recognise Periodicity as a proof that there will be no 6 in

the development of 1 : 7?

|

“How does it happen that

3 × 4 is

4 × 3?” |

“An dieser Stelle muß eine Primzahl kommen” –

“An dieser Stelle kommt || steht eine

Primzahl”. |

‘Gibt es einen Zufall in der Mathematik?’

|

How does the returning to the dividend show me the periodicity

of the quotient. |

Denke an den Fall wenn man mehrere Züge in einem Spiel zusammenzieht

& etwa im Schach gar nicht erst mit der ersten Position

anfängt. |

“Die Form ‘1 2 3 4 5’ paßt auf die Form Was für ein Faktum ist das, daß die Reihenfolge das Resultat nicht ändert. The process we are going through just does lead to the same result; – but so far as it “leads to the same result” we could imagine it to lead to a different 33 result.

And so far as we couldn't imagine it to lead to a

different result it doesn't lead to any result but shows

what it's like to lead to the same result.

I.e.: If we look at the Forms |

“How can you impose two rules on your

arithmetic unless you know that they must lead to the

same result?”

You wish to say: “These rules by their very nature, lead to the same result.” And you would therefore have recognised something about the very nature of them. |

Now it is time that you make a man look into the

case || working of these rules; that is, you can prove something

about them. |

“You go through this way of thinking & then you go

through another way of thinking which independently leads to the same

result.” |

123456 123456

2 2 2 |

After you have seen that 1000 : 3 must

lead to 333 is it a confirmation to calculate it & see what it

does?

Hadn't you calculated it by “seeing that it was

333”?

And what does it mean that one calculation confirms the result of the

other? 35

If you first see that the two calculations must lead to the same result is it a confirmation to find that they do?  |

“If this goes on this way & that goes on that way they

must meet there!” |

25 25 25 25 ‒ ‒ ‒ 16 times 16 16 16 16 25 times They must meet at the end. “Are you surprised that they meet? Didn't you know that they had to meet?” |

“I wasn't surprised I always followed the

25s while going on with the 16s.”

36 |

Can we try whether it does? |

Can we imagine the same calculation to lead twice || the

second time to a different result? |

The question is really whether there can be a “must” in

a proposition about the

37

nature of things. |

“In the sense in which they ‘must’

lead, we can't say

they do lead. |

Wir nehmen ein falsches Verhältnis von Prozeß

& Resultat an.

Denn es heißt nicht daß ein gewisser Prozeß zu einem bestimmten Resultat führen muß. |

Denn ein Prozeß muß nur dazu führen daß er

geschehen ist. |

Ich kann mir eine Blume auf gewisse Weise gewachsen

denken.

Und das Wachstum ist dann ein Prozeß dessen Ende der

Zustand der Blume ist. |

In welchem Sinne ist es möglich nicht zu wissen wohin ein

mathematischer Vorgang führt.

Man könnte antworten es ist möglich nicht zu wissen, wohin er führen

wird aber nicht, nicht zu wissen wohin er führt.

In one sense you can't know the process without knowing the result, as the result is the end of the process. In 39 the other you may know a process

& not know the result. |

In mathematics we object to say these processes have the

… |

A calculation leads to a result mathematically apart

from the fact whether I have actually performed it. |

‘If I say this calculation must lead to this result it

has already led to

it.’ |

If I say ‘this calculation must lead to the same result’

by “this calculation” I am referring to

whatever I call a method of calculating. |

Does calculating that there isn't a six … confirm

the result that there couldn't be? |

“You already see what happens, it must always go on like

this.”

Now suppose you actually went on would this confirm what you saw

before? |

A man says, “I see that the two calculations so far agree

but I don't know why they should go on agreeing”.

Shall we say that he doesn't see a truth

which the other sees? –

He tries always again & again.

We ask him: “But don't you see that you

must get to the same result again?”

Should we say that he must go the long way of experience, where we go the shorter one of seeing? 41 |

“If the multiplication led to this result once, it

must lead to it || the same result

again.” |

“What is the criterion of

periodicity?”

Here we are inclined to think that we have a criterion the reappearance of

the remainder & the actual periodicity

i.e., the repetition ad inf. of the period.

|

The infinite & the huge.

Absolute idea of large & small. |

“These people don't see a simple truth

….” |

But not “because it had to lead through to

the same result”. |

It is a remarkable fact that people almost always agree how to

count. |

Supposing I said this is the 100th house of this street, although

there are only 5 houses built. 43 |

Am

I to be guided by this or by this?

And how do I know that they will guide me to the same result? Am

I to be guided by this or by this?

And how do I know that they will guide me to the same result?We have a general kind of idea of how it goes on; but can't this after all be contradicted by the actual detailed calculation? Isn't there a danger of it going wrong after all? What is the truth which we see (& which is ‘obvious’)? That This shows us that this was justified”. But then we leave behind us these justifications. At first imagination accompanies us a stretch & then we are left alone. |

If there are 777 in the first 100 places there are 777 in the infinite

development. 44 |

The process of calculation can || may be regarded as a

process where there is no compulsion or being guided & on the other

hand, as a process where we move under some strict

guidance. |

“If I follow this chain of steps it's bound

to lead me there.” |

“The question are there 777 in π is all right

because surely there either are 777 in π or

there aren't”.

Queer use of p ⌵ ~p.

Images characteristic for this statement.

It really means: “The question is all right because there is a method of verifying it although we can't use it.” |

“The third place of π is 4

whether I know it or not.” |

“What if we had proved it to be self-contradictory

that there should be no 777 in π,

mustn't we then say that there are 777?” |

Our prose expressions in mathematics are highly metaphorical.

|

“Every algebraic equivalent has a

root”.

Is this to be called a proposition?

46

The question corresponding to this proposition as answer is vague. But once the proposition this piece of mathematics has been done we are inclined to call it the proof that our question had to be answered is the positive. But, as one might say, there was much less in the question than there is now in the answer. – Compare this with: “Is 25 × 25 = 600?” |

Propositions which seem only to

have sense if their truth or falsehood is known. |

What kind of proposition will the

proposition be that there can't (or

must) be 777 in π. |

Will it be possible e.g. to calculate whether any

given proposition of digits occurs or how often

it does. |

Relation between proof showing that 777 must be between n &

m & proof that they are at the

vth place (v being between n

& m). 47 |

Negation of a mathematical proposition &

fault in a calculation. |

“Question” corresponds to

“investigation”. |

Heptagon must there have been an investigation. |

“Is 5. a cardinal

number?” |

There is a contradiction between the normal use of the word

“proposition”,

“question.” 11 |

“Wouldn't one like to know with real

certainty whether the other had || has

pains?” |

Feeling of pastness.

“The experiences bound up with the gesture etc.

aren't the experience of pastness, for they could be there without

the feeling of pastness”. –

But, on the other hand, would it be that experience

of pastness without those experiences bound up with the

gesture? –

Why should we say that the

characteristic || essential part is the

part outside those experiences?

Isn't the experience at least partially described if I have

described the gestures etc.? |

Auch so: Die Worte “lang ist es her –”

rufen in mir manchmal ein bestimmtes Gefühl

wach.

Manchmal nicht.

Aber wenn sie es wachrufen so sind sie, ihr ◇◇◇ Teil der

charakteristischen Erfahrung. |

Sprechen mit Andern & mit mir selbst: “Wenn

ich eine gewisse Erfahrung habe, gebe ich (nur) das Zeichen

✢ ….” 12. |

When one says “I talk to myself”

one generally means just that one speaks & is the only

person listening. |

If I look at something red & say, to myself, this is red, am I giving

myself an information?

Am I communicating a personal experience to myself.

Some philosophising people might be inclined to say that this

is the only real case of communication of personal experience because only I

know what I really mean by ‘red’. |

Remember in which special cases only it has sense to

inform a person || an other

person that the colour he sees now is red. |

One doesn't say to oneself “This

is a chair. –

Oh really?” |

Wie kann ich denn einer Erfahrung

(etwa einem Schmerz) einen

Namen geben?

Ist es nicht als wollte ich ihm, etwa, einen Hut aufsetzen?

|

Nehmen wir an man sagte: “Man kann

13 ihm nur indirekt einen Hut

aufsetzen” so würde ich fragen: Glaubst Du daß man je

auf die Idee gekommen wäre davon zu reden wenn man nicht daran gedacht hätte

daß man dem Menschen der Schmerzen hat einen Hut aufsetzen kann?

Zu sagen man könne dem Schmerz nur indirekt einen Hut aufsetze macht es

erscheinen als gäbe es dennoch einen direkten Weg der nur tatsächlich

nicht gangbar sei.

◇◇◇◇◇◇ |

The difficulty is that we feel that we have said something about the

nature of pain when we say that one person can't have

another person's pain.

Perhaps we shouldn't be inclined to say that we had anything

physiological or even psychological but something

metapsychological metaphysical.

Something about the essence, nature, of pain as opposed to its causal

connections to other phenomena. |

Es scheint uns etwa als wäre es zwar nicht falsch sondern unsinnig zu

sagen “ich fühle seine Schmerzen”, aber als wäre dies so

infolge der Natur

14 des Schmerzes, der Person

etc..

Als wäre also jene Aussage letzten Endes doch eine Aussage über die Natur

der Dinge.

Wir sprechen also etwa von einer Asymmetrie unserer Ausdrucksweise & fassen diese auf als ein Spiegelbild des Wesens der Dinge. |

Intangibility of impressions.

(Anguish)

Some we should say were more tangible than

others.

Seeing more tangible than a faint pain; & this more tangible

than a vague fear, longing etc.

In what way are these intangible experiences less easy to communicate to describe than the ‘simpler’ ones? In what way do we use the phrase: “This experience is difficult to describe.” And can an experience || And can it be even impossible to describe certain experiencesbe ever ? |

Was für einen Sinn hat es zu sagen diese Erfahrung ist nicht beschreibbar? Wir möchten sagen: sie ist zu komplex, zu subtil. |

“Diese Erfahrung ist nicht mitteilbar, aber ich kenne

sie, – weil ich sie habe.” 15 |

“Es gibt die Erfahrung, & die Beschreibung der

Erfahrung. –

Daher kann es nicht gleichgültig sein, ob der Andere die selbe Erfahrung

hat, wie ich, oder nicht; – & daher kann

es || muß es wenn ich mit mir selbst rede auf

diese || meine Erfahrung ankommen.

Es muß dabei eine entscheidende Rolle spielen daß

ich diese Erfahrung kenne (während ich mit der des Andern nicht direkt

vertraut bin).” |

Kann man sagen: “In dem || das was ich über die Erfahrung des Andern sage, spielt seine

Erfahrung (selbst) nicht hinein.

In dem || das was ich über meine Erfahrung sage spielt

sie || diese Erfahrung selbst

hinein.”?

“Ich spreche über meine Erfahrung, sozusagen, in ihrer Anwesenheit” || in ihrem Beisein. |

Wie wenn jemand sagen würde: “Es gibt nicht nur die

Beschreibung des Tisches sondern auch den Tisch.” |

“Es gibt nicht nur das Wort ‘Zahnschmerz’,

es gibt auch such a thing as || etwas wie den

Zahnschmerz selbst.” || … es gibt auch

Zahnschmerzen.” 16 |

Es scheint, daß, da ich etwa eine Erfahrung nicht beschreiben kann, sie

aber habe, daß ich sie daher genauer kennen kann, als irgend ein

Anderer.

Aber was heißt, die Erfahrung kennen, wenn es nicht heißt,

sie beschreiben & nicht heißt, sie haben.

Gibt es eine Kenntnis der Erfahrung, die wir nicht mitteilen können? |

Hat es Sinn zu sagen “ich kenne diese Erfahrung besser || genauer als irgend ein Anderer sie kennen

kann”?¤

Gibt es Erfahrungen die der Andere ebensogut kennen kann wie ich

& solche, die er nicht so gut kennen

kann?

Heißt das: er kann diese selbe komplizierte Erfahrung nicht

haben? –

Es heißt wohl: “Er kann sie haben, aber wir können

nie || nicht wissen, daß er gerade || genau

diese gehabt hat”.

Z.B. scheint es als könnten wir

sagen: “Wir können in einem Sinn wissen daß er gerade

diese einfärbige, glatte, rote Fläche sieht,

aber nicht, daß er genau dieses Flimmern sieht.

Weil sich das genaue Gesichtsbild beim Flimmern || des Flimmerns nicht beschreiben

läßt. |

Es gibt ja auch den Fall, in dem wir ein Gesichtsbild genauer durch

ein gemaltes Bild als durch

17 Worte

beschreiben können. |

Wie ist es damit: “Man kann eine Figur

genauer mit Hilfe von Maßzahlen als ohne diese

beschreiben”. |

Aber die Erfahrung, die ich habe scheint eine Beschreibung dieser Erfahrung, im gewissen

Sinne, zu ersetzen.

“Sie ist ihre eigene Beschreibung”. |

Vermischen wir hier nicht zwei Dinge: die Zusammengesetztheit

der Erfahrung &, was man ihren ursprünglichen

Geschmack || Ton || flavour nennen könnte?

Ihre eigentliche natürliche Farbe? |

Es ist die Auffassung, daß von der ursprünglichen Erfahrung

nur ein Teil bei || in der Mitteilung

erhalten bleibt, & etwas anderes von ihr verloren

geht.

Nämlich eben ‘ihr timbre’, oder wie

man es nennen möchte.

Es kommt einem hier so vor als könnte man,

sozusagen nur die farblose Zeichnung vermitteln & der

Andere setzte in sie seine Farben ein.

Aber das ist natürlich (eine) Täuschung. |

Aber können wir nicht wirklich sagen, wir hätten in dem Andern durch

unsere Beschreibung ein Bild hervorgebracht aber wir können nicht

wissen ob dieses Bild nun

18 genau das

gleiche ist, wie das unsere?

Denken wir hier an den Gebrauch des Wortes

“gleich” in solchen Sätzen

wie: “Diese Kreise sind dem Augenschein nach

ganz gleich.” |

Hierher gehört auch, daß wir gewöhnlich unser Gesichtsbild nicht als etwas

in uns empfinden wie etwa einen Schmerz im Auge daß wir aber wenn wir

philosophieren geneigt sind diesem Bild

gemäß zu denken. |

The

‘if-sensation’.

Compare with the ‘table-sensation’.

There is the question “What's the

table-sensation like” & the answer is a

picture of a table.

In what sense is the if-sensation analogous to the

table-sensation?

Is there a description of this sensation & what do we call a

description of it.

Putting the gestures instead of the sensation means

just giving the nearest rough

description there is of this || the

Experience. |

Example [“I have a peculiar feeling of pastness in my wrist.”] 19.

6) “We shall never know whether he meant this or

that”.

C died after the training in that room.

We say: “Perhaps he would have

reacted like B when taken into the

daylight.”

But we shall never know.

α) We should say this question was decided if he arose from his grave & we then made the experiment with him. Or his ghost appeared to us in a spiritualist séance & told us that he has a certain experience. β) We don't accept any evidence. But what if we didn't accept the evidence in 5) either & said (something like) “We can't be sure that he is the identical man who was trained in the room”, or: “he is the identical man but we can't know whether he would have behaved like this in the past time when he was trained”. 7) We introduce a new notation for the expression “If P happens then always (as a rule) Q happens. P didn't happen this time & Q didn't happen.” We say instead: “If P had happened Q would have happened”. E.g. “If the gunpowder is dry under these circumstances a spark of this strength explodes it. It wouldn't dry this time & under the same circumstances didn't explode.” We say instead “If the gunpowder had been dry this time it would have exploded”. The point of this notation is that it nears the form of this preposition very much to the form: “The gunpowder 20. was dry this time so it

exploded”.

I mean the new form doesn't stress the fact that

it did not explode but, we might say, paints a vivid picture of it exploding

this time.

We could imagine two forms of expression in a

picture language corresponding to the two kinds of

notations in the word language.

The second notation will be particularly appropriate

e.g. if we wish to give a person a shock by

making him vividly imagine what || that which

would have happened, stressing only slightly that it

hasn't

happened || didn't happen.

8) Someone might say to us: “But are you sure that the second sentence means just what the first one means & not just something similar or that & something else as well? (Moore) I should say: I'm talking of the case where it means just this, & this seems to me an important case (which you caused by saying what you have said). But of course I don't say that it isn't used in other ways as well & then we'll have to talk about these other cases separately. 9) Someone says –“lowering one's voice some 21

times means

that

what you say is less important than the rest

& in

other cases you lower your voice to show that you

wish to draw special attention to what you now say

.”We || It must be clear that our examples are not preparations to the analysis of the actual meaning of the expression so & so (Nicod) but giving them effects that “analysis”. 11) Have we now shown that to say in 5 “We can't know whether he would have behaved … ” makes no sense? We should say the sentence || to say this sentence under these circumstances has lost its || the point which it would have had under other circumstances but this doesn't mean that we can't give it another point. 10) We say “We don't || can't know whether this spark would have been sufficient to ignite that mixture; because we can't reproduce the exact mixture not having the exact ingredients or not having a balance to weigh them etc. etc.” But suppose we could reproduce all the circumstances & someone said “we can't know whether it would have exploded” as we can't know whether || & being asked why he said because under these circumstances it would have exploded then.” This answer would set our head whirling. We should feel he wasn't playing the same game with that expression as we do. We should be 22.

inclined to say “This makes no sense!”

And this means that we are at a loss not knowing what reasoning, what

actions go with this expression.

Moreover we believe that he made up a sentence analogous to sentences used

in certain language games not

noticing that he took the point away.

In which case do we say that a sentence has a point? That comes to asking in which case do we call something a language game. I can only answer. Look at the family of language games & that will show you whatever can be shown about the matter. |

12) (The private visual image.)

B is trained to describe his afterimage when he has looked say into

a bright red light.

He is made to look into the light, & then to shut his eyes

& he is then asked “What do you

see?”.

This question before was put to him only if he looked at physical

objects.

We suppose he reacts by a description of what he sees with closed

eyes. –

But halt!

This description of the training seems wrong for what if

23 I had had to describe my

own, not B's, training.

¤

Would I then also have said: “I reacted to the question by

… ” & not rather: “When I had

closed my eyes I saw an image & described

it”.

If I say “I saw an image & described it I say this as

opposed to the case where || in which I

gave a description without seeing an image.

(I might have lied or not.)

Now we could of course also distinguish these cases if B

describes an afterimage.

But we don't wish to consider now cases in which the mechanism of lying

plays any part.

For if you say “I always know whether I am lying

but not whether the other person is”, I

say: in the case I'm considering I can't be said

to know that I'm not lying, or let us say not saying the

untruth, because the dilemma saying the truth or the

untruth is in this case unknown to me.

Think of the fact || Remember that when

I'm asked “what do you see here” I

don't always ask myself: “Now shall I say the

truth or something else?”

If you say “but surely if you in fact speak the truth

then you did see something & you saw what you said you

saw”

I answer: How can I know that I see what I say I

see?

Do I have a criterion or use one

for the colour I see actually being

red? 24. |

13) We imagine that the expression

“I can't see what you see” has been given sense

by explaining it to mean: “I can't see what

you see being in a different position relative to the object we are looking

at”, or “ … having not as good eyes as

you”, or “ … having found as in … that

B sees something which we don't though we look at the same

Object.”

etc.

I can't see your afterimage might be explained to mean I

can't see what you see if I close my eyes meaning

you say you see a red circle, I see a yellow one.

14) Identity of physical objects, of shapes, colours, dreams, toothache. 15) (The thing || object we see) The physical Object & its appearance. Form of expression: different views of the same physical object are different objects seen. We ask “What do you see” & he can either answer “a chair”, or „this” (& draw the particular view of the chair). So we are now inclined to say that each man sees a different object & one which no other person sees, for even if they look at the same chair from the same spot it may appear different to them & the objects before the other mind's eye I can't look at. 16) (I can't know whether he sees anything 25

at all or

only behaves as I do when I see something.)

There seems to be an undoubted asymmetry in the use of the

word “I || to see” (&

all words relating to personal experience).

One can || is inclined to state this in the way that

“I know when I see something by just seeing it, without hearing

what I say or observing the rest of my behaviour whereas I know

that he sees & what he sees only by observing

his behaviour, i.e. indirectly”.

a) There is a mistake in this ◇◇◇: I know what I see because I see it”. What does it mean to know that. b) It is true to say that my reason for saying that I see is not the observation of my behaviour. But this is a grammatical proposition c) It seems to be an imperfection that I can only know ‒ ‒ ‒. But this is just the way we use the word ‒ ‒ ‒. – Could we then … if we could? Certainly. |

Does the person who has not learnt

language know || Should we say that the person who has not learnt the

language knows that he sees red but

can't express it? –

Or should we say: “he knows what he sees but

can't express it”? –

So besides seeing it he also knows what he

sees?

Imagine we described a totally different experiment; say this, that I sting someone with a needle & observe whether he cries out or not || makes a sound or not. Then surely it would interest us if the subject 26

whenever we || often when we

stung him saw, say, a red circle.

And we would distinguish the case when he cried out & saw a circle

from the case when he cried out & didn't see one.

This case is quite straightforward & there is no problem about it. || seems to be nothing problematic in it. |

If I say “I tell myself that I see red, I tell myself what I

see” it seems that after having told myself I now know better what

I see, am better acquainted with it, than before.

(Now in a sense this may be so …) |

“When he asked me what colours I saw,

I guessed what he meant || wished || wanted to know & told him.” |

“It is not enough to distinguish between the cases in which

B or I say that I see red & do see

red & the case in which I say this but don't

see red; but we must distinguish between the cases in which I see red, say I see red & mean to describe

what I see & the cases in which I don't mean

this. 27 |

Consider the case in which I don't say what I see

in words but by pointing to a sample.

Here again I distinguish now between the cases in which I ‘just

react by pointing’ & the case in which I see

& point. |

Now suppose I asked: “how do I know that I see

& that I see red?

“I.e. how do I know

that I do what you call seeing (& seeing

red)?”

For we use the word ‘seeing’ &

‘red’ between us. || in a game we play

with one another. |

Don't you say: “In

order to be a description of our personal experience

it || what we say must not just be

the || our reaction but must be

justified”?

But does the justification need another justification?

|

Suppose,

we play the game 2) & B calls out the

word “red”.

Suppose A now asks B: “do you only say

‘red’ or did you really see it?”. |

“Surely there are two phenomena: one, just speaking,

the other, seeing & speaking accordingly.”

Answer: Certainly we speak of these two cases but we shall

here have to show how

28 these expressions are used; or, in other

words, how they are taught.

For the mere fact that we possess a picture of them

does not help us as we must describe how || in what

way this picture is used.

More especially as we are inclined to assume a use different from the

actual one.

We have therefore to explain under what conditions we say: “I say ‘red’ but don't see red” or “I say ‘red’ & see red”, or “I said ‘red’ but didn't see red” etc. etc.. Imagine that saying red was often followed by some agreeable event. We found that the child enjoyed that event & often instead of ‘green’ said ‘red’. We would use this reaction to play another language game with the child. We would say “you cheat, it's red”. Now again we are dependent upon the subsequent reaction of the child. Such games are actually played with children: Telling a person the untruth & enjoying his surprise at finding out what really happened. |

But couldn't we imagine some kind of perversity in a child which

made it say red when it saw green & vice versa & at the 29

same time this not being discovered because

it happened to see red in those cases when we say green?

But if here we talk of perversity we could || might also

assume that we all were perverse.

For how are we or B ever to find out that he is perverse?

The idea is, that he ¤ finds out (& we do) when later on he learns how the word ‘perverse’ is used & now || then he remembers that he was that way all along. Imagine this case: The child looks at the lights: says the name of the right colour to himself in an aside & then loud the wrong word. It chuckles while doing so. This is, one may say, a rudimentary form of cheating. One might even say: “This child is going to be a liar”. But if it had not said the aside but only imagined itself pointing to one colour on the chart & then said the wrong word, – was this cheating too? Can a child cheat like a banker without the knowledge of the banker? |

“I can assure you that before when I said ‘I see

red’ I saw black.” 30 |

“He tells us his private experience, that experience which nobody

but he knows anything about”. |

“Surely his memory is worth more than our

direct criteria, as only he could know what he

saw.” |

¤ But let us see;– We sometimes say outside philosophy such things as “of course only he knows how he feels” or “I can't know what you feel”. Now how do we apply such a statement? Mostly it is an expression of helplessness like “I don't know what to do”. But this helplessness is not due to an unfortunate metaphysical fact, ‘the privacy of personal experience’, or it would worry us always || constantly. Our expression is comparable to this: “What's done can't be undone!”. |

We also say to the Doctor “Surely I must know

whether I have pains or not!”

How do we use this statement? |

“All right if we can't

talk in this way about someone else I can certainly say of myself that

I either saw red

31

at that time or didn't || had some other

experience.

I may not remember now, but at the time I saw one thing or the

other!”

This is like saying “one of these two pictures must have

fitted”.

And my answer is not that perhaps neither of them fits but that

I'm not yet clear about what ‘fitting’ in this

case means. |

Now is it the same case or are these different cases:

A blind man sees everything just as we do but he acts as a blind man

does & on the other hand he sees nothing & acts as a blind

man does.

At first sight we should say: here we have obviously two clearly

different cases although we admit that we

can't know which we have before us.

I should say: We obviously

use two different pictures which one || we could describe like

this: ….

But we use both || the pictures in

such same || a way that the two games

‘come to the same’. |

By the way, – would you say that he surely || certainly

knew that he was blind if he was so?

Why do you feel more reluctant about this statement? 32 |

“Surely he knew that he saw red but he

couldn't say so!” –

Does that mean “Surely he saw || knew that he saw

the colour which we call ‘red’ … ”

– or would you say it means “he

knew that he saw this colour” (pointing to a red

patch).

But did he while he knew it point to this patch? |

Use of: “He knows what colour he

sees”.

“I knew what colour I saw”

etc. |

“Nachdunkeln der Erinnerung” does

this expression make sense & in what cases. And isn't on the other hand the picture which we use quite clear in all cases? |

The case of old people usually having || getting memories of

the time in which they learnt to speak & understand speech:

a) They say or paint that such & such things have happened although other records always contradict them b) The memories agree with the records. Only in this case shall we say that they remember …. |

Suppose they paint the scenes they

33 say they remember & paint the faces

very dark;– shall we say that they saw them that dark or that the

colour had become darker in their memory? |

How do we know what colour a person sees?

By the sample he points to?

And how do we know what relation the sample is

meant to have to the original?

Now are we to say “we never know …”?

Or had we better cut these “we never know

… ” out of our language &

consider how as a matter of fact we are wont to use the word

“to know”? |

What if someone asked: “How do we || I know that what I call seeing red is not an

entirely different experience every

time & that I am not deluded

into thinking that it is the same or nearly the

same?”?

Here again the answer “I can't know & the

subsequent removal of the question”. |

Is it ever true that when I call a colour ‘red’ I

serve myself of memory?? || make use of

memory?? |

To use the memory of what happened

34 when we were taught language is

all right as long as we don't think

that this memory teaches us something essentially private. |

“Though he can't say what it is he sees

while he is learning № 1, he'll tell us afterwards what

he saw.

We mix this case up with the one: “When his

gag will have been removed he'll tell us what he

saw”. |

What does it mean ‘to tell someone what

one sees’?

Or (perhaps), ‘to show someone what one

sees’? |

When we say “he'll tell us what he

saw” we have an idea that then we'll know

what he really saw in a direct way

(“at least if he isn't

lying”). |

“He is in a better position to say what he sees than we

are.” –

That depends. – |

If we say “he'll tell us what he saw”, it is

as though he would now make a

35 use of

language which we had never taught him. |

It is as if now we got an insight into

something which before we had only seen from the outside. |

Inside & outside! |

“Our teaching || training connects the word

‘red’ (or is meant to connect it) with a

particular impression of his (a private impression an impression in

him).

He then communicates this impression– indirectly, of course–

through the medium of speech.” |

Where is the || our idea of “direct

& indirect communication” taken

from? |

How, if we said, as we sometimes might be inclined:

“We can only hope that this– indirect way of

communication really succeeds”.

|

We so long see the facts about the usage of our words crookedly

as || so long as we are still tempted

here to talk of direct & indirect. |

As long as you use the picture indirect-direct in this case you

can't trust yourself

36 about

judging the grammatical situation rightly otherwise.

|

Is telling what one sees something like turning one's

inside out?

And learning to say what one sees, learning to let others see inside

us? |

“We teach him to make us see what he sees”.

He seems in an indirect way to show us the object which he sees,

the object which is before his mind's eye.

“We can't look at it, it is in him.”

|

The idea of the private object of vision.

Appearance, sense-datum. |

The visual field.

(Not to be confused with visual space.) |

Telling someone what one sees seems like showing him, if indirectly, the

object which is before one's mind's

eye. |

The idea of the object before one's mind's eye is

absolutely bound || (firmly) tied up with

the idea of a comparison of such

objects in different persons compared to which the

comparison

37 really

used is an indirect one. |

Whence the idea of the privacy of sensedata? |

“But do you really wish to say that they are not

private that one person can see the picture before the

other person's eye?” |

Surely you wouldn't think that telling someone

what one sees is || could be a more direct way of

communicating than showing him by pointing to a sample! |

“He'll tell us later what it was he saw” means

that we'll get to know in a (comparatively) direct

& a sure way what he saw as opposed to the guesses we could

make before. |

We don't realize that the answer he gives us now is

only part of a game like № 1 only more complicated.

38 |

We don't deny that he can remember a dream || having dreamt so

& so before he was born.

Denying this to us would be like denying that he can say he remembers

having dreamt so & so before he was born.

I.e. we don't deny that he can make this move but we say that the move alone or together with all the sensations, feelings etc. he might have while he is making it does not tell us what game it is a move of. || to what game the move belongs. We might e.g. never try to connect up a statement of this sort with anything past (in an other sense). We might treat it as an interesting phenomenon & possibly connect it up with the persons writing in a Freudian way or on the other hand we may look for some phenomena in the brain of the embryo which might be called dreams etc. etc.. Or we may just say: “old people are liable to say such things” & leave it at that. |

Suppose now someone remembered that yesterday he called

red ‘green’ & vice versa but that this

didn't appear as he also saw green what today he

sees red & vice versa.

Now here is a case in which we might be inclined to say that we

39 learn from him today something about the

working of his mind yesterday, that yesterday we judged by the outside while

today we are allowed to look at the inside of what

happened.

It is as though we looked back but now got a glance at something that was

closed to us || covered up yesterday. |

If I say what it is I see how do I compare what I say with what I see in

order to know whether I say the truth?

Lying about what I see, you might say, is knowing what I see & saying something else. Supposing I said it just consists of saying to myself ‘this is red’ & aloud ‘this is green’. |

Compare lying & telling the truth in the case of telling what

colour you see with the case of describing a picture which you saw or

telling the right number of things you had to count. |

Collating what you say & what you see. |

Is there always a collating? 40 |

Or could you call it giving a picture of the colour I see if I say the

word “red”?

Unless it be a

picture by its connection with a sample. |

But isn't it giving a picture if I point to a

sample? |

“What I show reveals what I see”; – in

what sense does it do that?

The idea is that now you can so to speak look inside me.

Whereas I only reveal to you what I see in a game of revealing &

hiding which is altogether played with

signs of one category.

“Direct – indirect”.

|

We are thinking of a game in which there is an inside in the normal

sense. |

We must get clear about how the metaphor of revealing (outside

& inside) is actually applied by us; otherwise we shall be

tempted to look for an inside behind that which in our metaphor is the

inside. |

We are used to describing the case by means of a picture which say

41 contains 3 steps.

But when we think about language we forget how this

picture is actually applied in practical cases.

We then are often tempted to apply it as it wasn't

meant originally || originally meant & are puzzled about a third

step in the facts. |

“I see a particular sense-datum || image || thing & say a particular

thing”.

This is all right if I realise

the way in which I specify what I see & what I say. |

“If he had learnt to show me (or tell me) what he sees, he

could now show me.”

Certainly, – but what is it like to show me what he sees?

It is pointing to something under particular circumstances.

Or is it something else (don't be misled by the

idea of indirectness).

You compare it with such a statement as: “if he had learnt to open up he could now open up & show me what's inside || I could now see what's inside. I say yes, but remember what opening up in this case is like. |

But what about the criterion whether there

is anything inside or not?

Here we say “I know that there is something

42 inside in my case.

And this is how I know of the ‘inside’ at all first

hand”. || And this is how I have first

hand knowledge of the inside at all.” ||

This is how I know about an inside & am

led to suppose it in the other person too.”Further we are not inclined to say that only hitherto we have not known the mind of an other person but that the idea of this knowledge is bound up with the idea of myself. |

“So if I say ‘he has toothache’ I am supposing

that he has what I have if I have toothache.”

Suppose I said: “If I say ‘I

suppose’ he has toothache, I am supposing that he

has what I have if I have toothache”, – this

would be like saying “If I say ‘this cushion is

red’ I mean that it has the same colour which the sofa has if it is

red”.

But this wasn't what I intended to

say || was meant with the first sentence.

I wished to say that talking about his toothache at all was based

upon a supposition, a supposition which by its very

nature || essence could not be

verified. |

But if you look closer you will see that this is an entire

misrepresentation of the use of the word

“toothache”. 43 |

Can two people have the same afterimage? |

Language-game ‘Description of

imaginings || the picture before one's

mind's eye.’ |

Can two persons have the same picture before their

mind's eye. |

In which case would we say that they had two images exactly alike but not

identical? |

The fact that two ideas seem here inseparably bound up suggests to us that

we are dealing with one idea only & not with two & that by a

queer trick our language suggests a totally different

structure of grammar than the one actually

used.

For we have the sentence that only I can know directly my

experience & only indirectly the experience of the

other person.

This || Thus

language suggests 4 possible combinations but rules out

2.

It is as though I had used the 4 letters

44 a b c d to denote two objects only but

by my notation somehow suggesting that I am

talking of 4. |

I do this by spreading the use of the word I over all

human bodies as opposed to

L.W.

alone. |

I want to describe a situation in which I should

not be tempted to say that I assumed or believed that the other had what I

have.

Or, in other words a situation in which we would not speak of

my consciousness & his

consciousness.

And in which the idea would not 45 occur to

us that we could only be conscious of our own consciousness. |

The idea of the ego inhabiting a body to be abolished. |

If what any consciousness ¤ spreads over all human bodies then

there won't be any temptation to

use the word ‘ego’. |

Let's assume that hearing was done by no organ of the body we

know of. |

Let us imagine the following arrangement: If it is absurd to say that I only know that I see but not that the others do, – isn't this at any rate less absurd than to say the opposite? |

The idea of the constituent of a fact:

“Is my person (or a person) a constituent of the

fact that I see or not”.

This expresses a question concerning the symbolism just as if it were a

question about nature. |

“Es denkt”.

Ist dieser Satz wahr & “ich denke”

falsch? |

Language-game: I

paint, for myself, what I see.

The picture doesn't contain me.

|

A board game in which only one man is said to play

the other to ‘answer’.

|

What if the other person always correctly described what I

saw, & imagined, would I not say he knows what I

see? –

“But what if he describes …

13

|

Editorial notes

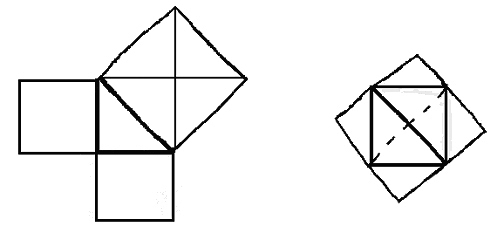

1) Ms-148, pages 4r-4v contain a number of figures and tables which are not included in the transcription.

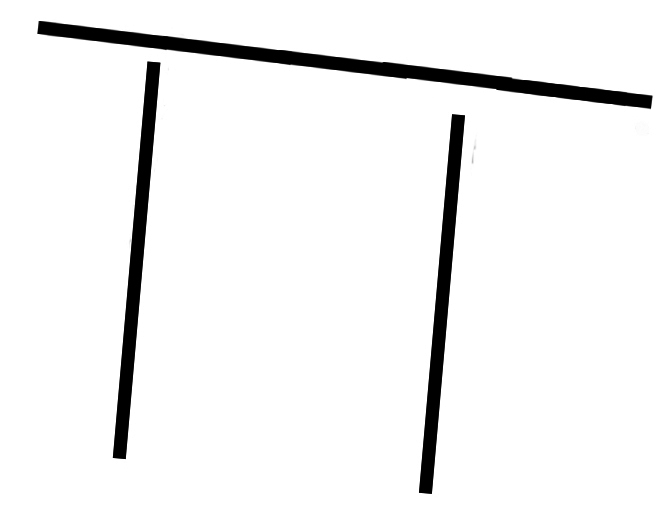

2) Ms-148, page 7r contains a number of geometrical proof drawings which are not included in the transcription.

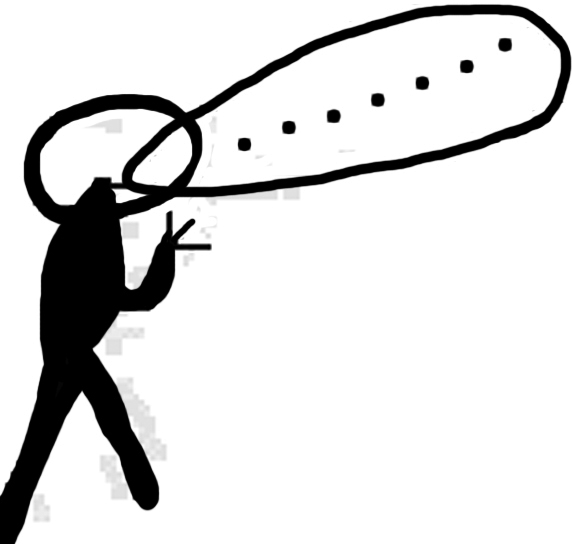

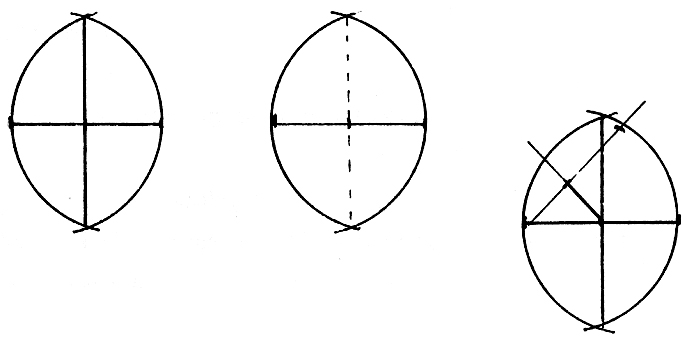

3) Ms-148, page 10r contains a number of technical figures as well as a multiplication formula which are not included in the transcription.

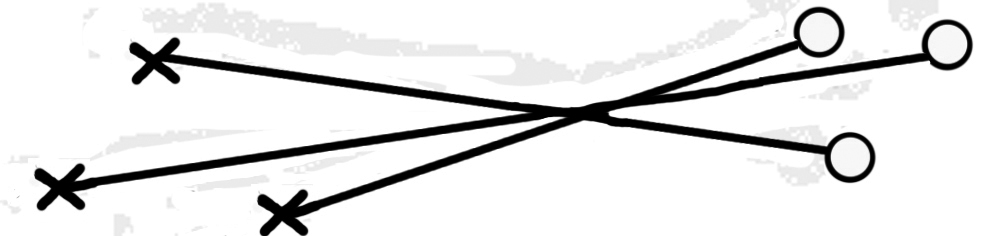

4) Ms-148, page 11v contains additional drawings and formulas which are not included in the transcription.

5) Ms-148, page 12v contains one additonal figure which doesn't seem related to the surrounding text and is not included in the transcription.

6) Ms-148, page 13r contains a number of figures which are not included in the transcription.

7) Ms-148, page 14r contains a number of figures which are not included in the transcription.

8) Ms-148, page 14v contains figures and calculations which are not included in the transcription.

9) Ms-148, page 16v contains a figure which doesn't seem related to the surrounding text and is not included in the transcription.

10) Ms-148, page 17r contains a figure which doesn't seem related to the surrounding text and is not included in the transcription.

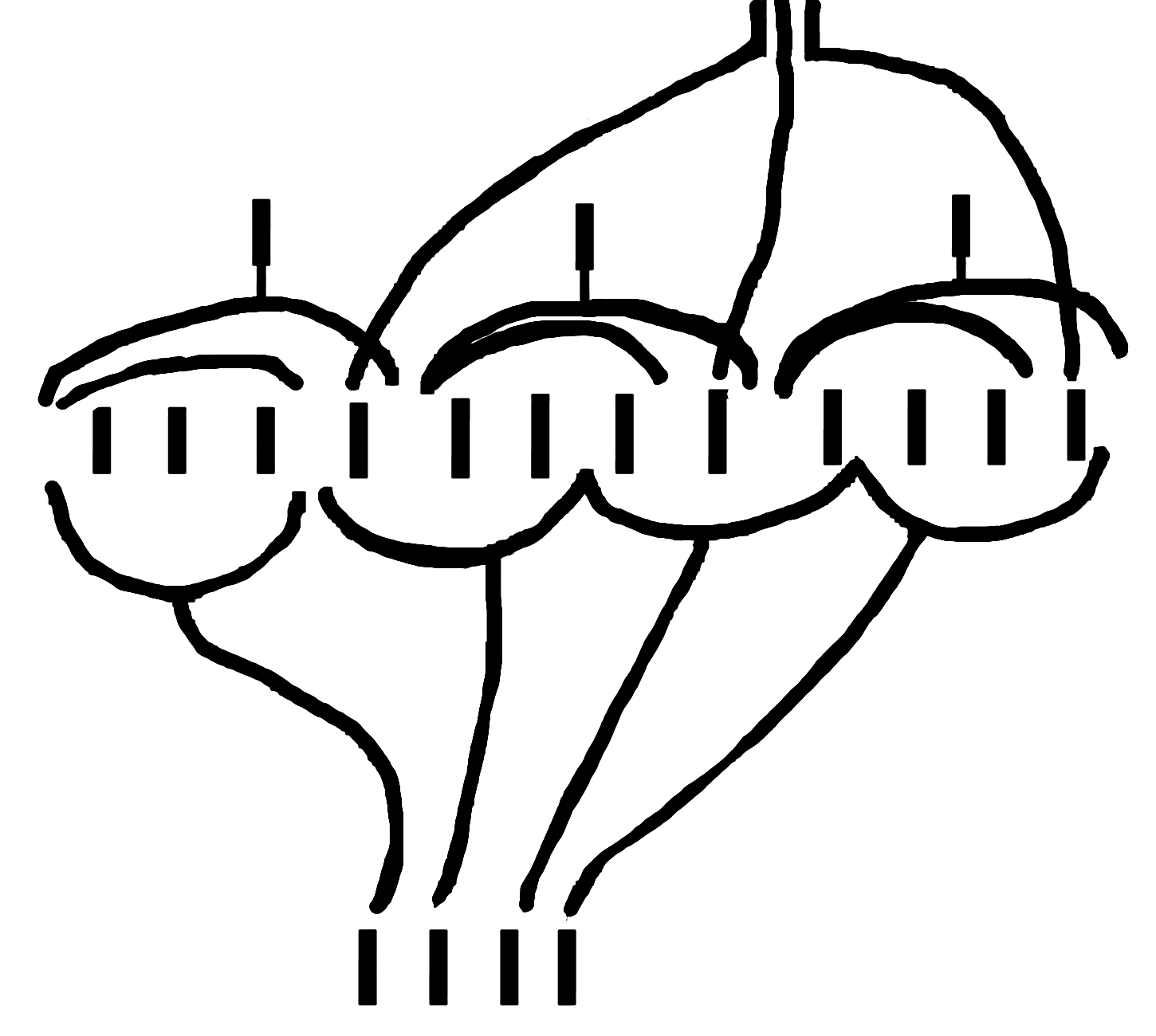

11) Ms-148, page 20v contains further calculations which don't seem related to the surrounding text.

12) Ms-148, page 21r contains additional calculation and figure scribbles which are not included in the transcription.

13) Continuation in Ms-149,1r.