1 Wenn wir uns fragen; worin besteht der Eindruck, den uns ein Wort macht, so denken wir zuletzt daran || an das, was wir sehen, wenn wir das Wort anschauen. Wir nehmen an das Bild des Wortes selbst sei ziemlich nebensächlich & der Eindruck liege irgendwie hinter dem Wortgestalt || Wortbild. Und diesen Fehler machen wir immer wieder. Aber die Gestalt eines Wortes, das wir – wie alle Wörter der gewöhnlichen Sprache – unzählige male gesehen haben, macht uns einen tiefen Eindruck. Denke nur an die Schwierigkeiten, die wir empfinden wenn die Rechtschreibung geändert wird. Solche Änderungen sind als Sakrileg empfunden worden. Freilich nur gewisse Zeichen machen uns einen tiefen Eindruck, andere nicht. Ein neu erfundenes Zeichen etwa “ ⌵ ” für “oder” kann ohne in uns etwas aufzuregen durch ein beliebiges anderes ersetzt werden. Denke daran daß das geschriebene || gesehene Wort uns in ähnlicher Weise vertraut ist wie das gehörte. Denke an Esperanto & wie seltsam es uns anmutet einen Ausdruck der Herzlichkeit in diese Kunstsprache übersetzt zu hören. Wir könnten ja auch nicht den Händedruck willkürlich durch ein anderes Zeichen des Abschieds ersetzen. Das hängt damit zusammen, daß wir 2 uns das Gefühl der Trauer als etwas hinter

den Empfindungen des Weinens, schweren Atmens etc.

etc. vorstellen & diese geneigt sind als etwas

Nebensächliches zu vernachlässigen.

Auch hängt das mit der Frage zusammen ob der Eindruck || der Ausdruck des Gesichtes  gesehen wird oder hinter dem gesehenen gefühlt.

Denke an

gesehen wird oder hinter dem gesehenen gefühlt.

Denke an  & …1 & …1

|

Wenn wir in gewöhnlicher Schrift einen englischen Satz lesen, so

fühlen wir dabei eine wohlbekannte

Erfahrung || Empfindung oder Erfahrung || können wir dabei eine

wohlbekannte Empfindung oder Erfahrung haben.

Was heißt das: “Wir haben da eine ganz bestimmte Erfahrung”?!! in wiefern bestimmt? Lies eine Reihe gewöhnlicher etwa englischer Sätze in gewöhnlicher Schrift. Du wirst dann die Erfahrung des Lesens empfinden, nämlich eine fortlaufende, quasi gleichbleibende, Erfahrung. |

Worin besteht der Ausdruck eines Gesichts, eines Worts. |

Ein ‘bestimmter’ Eindruck, im Gegensatz wozu? ‘Das Gesicht hat einen bestimmten 3 Ausdruck; – im Gegensatz wozu?

Man kann die Aufmerksamkeit auf den Ausdruck des Gesichts heften. Was heißt das? Was tut man da? Es ist ähnlich wie || als wenn man es plastisch sähe. |

Ist der Ausdruck zum rein Visuellen addiert? –

Nun, weißt Du daß er addiert ist? –

Also ist der Fall verschieden von dem im welchen ich etwas sehe

& zugleich Schmerzen im Magen empfinde. |

“Wenn Du diesen Strich machst, so ändert das den Ausdruck des

Gesichts ganz”.

“Wenn Du diesen Strich ziehst so ändert sich der Ausdruck dieser Tiere ganz”. |

Nehmen wir an ich sage: der Eindruck (Ausdruck) ist durch

unsere Attitude zu dem Bild bestimmt.

Wechselt diese durch einen neuen Strich so sagen wir

es wechselt der Ausdruck.

Was aber an dieser Erklärung wesentlich ist sehen wir daran daß wir verschiedene Annahmen mache können. Wir können z.B. annehmen unser Gesicht mache immer ein gezeichnetes Gesicht nach. Aber es genügt auch wenn wir annehmen, daß ein neuer 4 Strich die ¤ Art & Weise etwa

den Weg ändert wie unser Auge immer wieder über die

Zeichnung gleitet. |

“Ein Punkt an diesen Ort ändert den Ausdruck, aber ein Punkt hier

ändert ihn nicht.” |

“Früher war der Ausdruck freundlich, jetzt ist er

traurig”.

Heißt das: ‘ich weiß daß ein trauriger Mensch so aussieht

& ein freundlicher so’? – |

Man könnte sagen: durch diesen Strich wird unsere

Erfahrung beim Sehen des Bildes in einer anderen Weise geändert als durch

einen ‘nichtssagenden’ Strich & diese

Änderung ist ähnlich der welche geschieht

wenn durch den Strich die räumliche Erscheinung der Zeichnung

geändert wird. |

Es ist das Wort ‘bestimmt’, welches wir verstehen

müssen. |

Ich lese etwa eine Reihe gewöhnlicher Sätze & beobachte mich dabei

selbst.

Ich merke, ich tue “etwas ganz

bestimmtes”, d.h. immer ungefähr

das Gleiche.

5

Es ist, als sagte ich: Wenn ich schreibe tue ich immer ungefähr das Gleiche. D.h. ich bewege meine Hand immer in ungefähr der gleichen Weise. |

Vergleiche die Familie dessen

was man

‘Schrift || Schreiben’ nennt mit der Familie

‘Lesen’. |

Wir fühlen das Gleichbleiben der Erfahrung. |

Änderung der Interpunktion verglichen mit einer Änderung der

Zeichnung die den Gesichtsausdruck ändert.

(“Der Schülero sagt der

Lehrero↙ ist ein

Esel.”)

Nicht ein Wissen ist es daß uns die Änderung bedeutsam

erscheinen läßt. |

Gegensatz der Ausdrücke. –

Gegensatz: Ausdruck – kein Ausdruck. |

Das Eine ist: Die Besonderheit des

Eindrucks verführt uns zu der Frage: was ist das

wesentliche des Lesens.

Das Andere: Ich muß die Rolle des typischen Beispiels klarer machen. Nämlich: die Rolle die Zuerst glaubt man nämlich man rede von einem Gemeinsamen & es ist das Ideal dieses anzugeben darzustellen. Dann aber ist das Feststehende nicht mehr ein Gemeinsames sondern ein Beispiel. (Sozusagen ein Zentrum der Variationen.) |

Die geschriebenen Wörter einer mir geläufigen Sprache sind mir

wohlbekannte Gesichter.

Und sie zu lesen sind mir wohlbekannte

Erlebnisse.

Wenn ich gefragt würde, was tue ich besonderes wenn ich die Wörter

lese, müßte ich sagen: ich sehe sie & spreche sie aus.

Und die Hauptsache des Erlebnisses liegt in der Wohlbekanntheit der

Wörter.

Aber diese Wohlbekanntheit ist eine besondere im besondern Fall sie ist

z.B. nicht das Erlebnis der Wohlbekanntheit

eines Gesichts & hier gibt es ja auch verschiedene

Fälle.

Geläufige Schrift zu lesen ist ein besonderes Erlebnis

anders z.B. als etwas zu

buchstabieren oder eine graphische Darstellung

ablesen etc. 7

|

“Ich weiß nicht, das Wort kommt mir auf einmal so fremd

vor”. – |

Es ist ganz abgesehen vom Lesen eine andere Art des Erlebnisses,

wenn der Blick über ihm geläufige Wortbilder gleitet als über

fremde. |

Was heißt das: “das Lesen einer uns geläufigen Sprache ist

ein ganz besonderes Erlebnis”?

D.h. wir haben beim lesenden Durchlaufen der Zeilen

ein gleichförmiges

Erlebnis, & es unterscheidet sich vom Durchlaufen

beliebiger anderer Formenreihen.

Es wäre auch unrichtig zu sagen, daß das Lesen einfach darin

bestehe, daß wir Zeichenreihen durchlaufen & uns dabei Laute

einfallen.

Denn wenn ich die Reihe Und diese Art des Erlebnisses ist charakteristisch für jedes fließende Lesen alles dessen was wir für gewöhnlich ‘Schrift’ nennen; aber nicht für das ‘Lesen’ überhaupt.2 8 |

Vergleiche ‘Lesen’ &

‘Bild’.

Auch in diesem Fall ein eng begrenztes Gebiet an welches wir vorerst

denken, dann aber ein Drang der uns in immer weitere Ferne zieht.

|

Kreise. |

Regel Glied eines Systems. |

“Es ist eine Einstellung sich dem Befehl wie er auch

lauten mag hingeben”.

Beispiel des Sich-leiten-lassens. Die Hand leiten lassen. Maschine. |

Betrachte einen allgemeinen Satz, wie “die Regel leitet uns, wenn

sie das Glied

9

eines Systems ist”!

Was sind die Beispiele dafür?

Wie gehen sie in die Umgebung über? |

Wenn wir die gewöhnliche Schrift lesen

geschieht immer ein & dasselbe & man könnte

sagen: beobachte doch was geschieht & Du wirst sehen worin das

Lesen besteht.

Du hast sozusagen Zeit genug um es zu

beobachten.

Nun was sehe ich da? (Da ist etwas interessant: daß man nicht im Stande ist ein geschriebenes oder gedrucktes Wort anzusehen ohne es zu lesen.) Ich gehe mit meinem Blick der Zeile entlang & schon das geschieht nicht so wie wenn ich ihn einer beliebigen Reihe von Bildern entlang führe (ich rede hier nicht von dem was experimentell durch Beobachtung der Augenbewegung festgestellt werden kann), der || . Der Blick gleitet möchte || könnte man sagen besonders reibungslos & doch nicht flüchtig || widerstandslos ohne hängen zu bleiben & doch rutscht er nicht (die Wohlbekanntheit der Wortgestalten, – anders wieder wenn man von rechts nach links liest). Dabei geht ein ganz unwillkürliches ‘Sprechen in der Vorstellung’ vor sich. Und so verhält es sich wenn ich deutsch, englisch, französisch, & gedruckt, 10 geschrieben in

lateinischer Schrift oder gotischer

Schrift lese.

Was aber von dem allem ist für das Lesen als solches wesentlich? Nicht ein Zug der in allen Fällen von Lesen vorkommen müßte. || vorkäme. |

Verstehen

Bedeutung Denken Erwarten Wünschen Fürchten Glauben Überzeugung 11

|

A: “Warum nennst Du diese beiden Farben

‘rot’?” –

B: “Weil eine

gewisse Ähnlichkeit zwischen ihnen besteht.” ¥ |

Was heißt es “diese beiden Farben sind ähnlich”; –

wie gebraucht man diesen Ausdruck? |

“Die beiden Farben haben ein Element gemeinsam & das

nenne ich ‘rot’”. |

A: “Diese beiden Farben sind doch sehr

ähnlich”.

B: “Ich finde sie sehr

verschieden”. |

Warum nennt man das Suchen im Gedächtnis ein

‘Suchen’? |

Warum nennt man eine Stimmung “trübe”?

Wie wenn man sagt, “weil beide das Wetter & die Stimmung uns denselben Eindruck machen”? Besteht die Gleichheit des Eindrucks nicht zum Teil gerade darin daß wir geneigt sind in beiden Fällen das gleiche Wort & in ähnlichen Verbindungen zu gebrauchen? Auch darin daß wir das Wort im gleichen Ton sagen. 12 |

“Ach Sie sind's!” |

(Die Problematik der Philosophie ist die Problematik des

Witzes.) |

Wie ist es wenn sich uns ein Vergleich aufdrängt?

Etwa der des ‘Suchens’ im Gedächtnis. |

Das Wort ‘gleichsam’.

“Er schaut gleichsam trübe aus”.

“Ich möchte immer sagen

‘trübe’”. |

Eine geistige Spannung.

Wir würden wahrscheinlich sagen sie sei etwas ähnlich wie eine

körperliche Spannung.

“Nun weiß ich auch warum ich das immer ‘eine Spannung’ nennen wollte.” (Ich habe etwa herausgefunden, daß dabei gewisse Muskeln gespannt sind. – Aber das wußte ich eben nicht als ich geneigt war es Spannung zu nennen.) 13 |

⍈

“Wenn wir in beiden Fällen von

‘trübe’ || ‘schwarz’ reden,

so gebrauchen wir das Wort in verschiedener Bedeutung.”

–

Was ist das Kriterium für den Gebrauch in

verschiedener Bedeutung?

|

Oder auch: Wie weißt Du das? oder besteht der Gebrauch

in verschiedenen

Bedeutungen eben darin?

Was willst Du sagen? |

Ich würde nun als Erklärung

Verschiedenheiten der beiden Spiele

aufzählen || hervorheben.

In der einen z.B. legt man etwas Schwarzes an das andere um zu sehen ob die beiden 14 gleich sind im andern Spiel ist dies nicht

der Fall.

Es heißt also mein Satz: Wenn Du das Wort

‘schwarz’ in beiden

Verbindungen gebrauchst so kann ich Dich auf andere

Verschiedenheiten in den beiden Spielen aufmerksam machen. |

Darauf aber gäbe es keine Antwort, wenn nun jemand sagte

“aber ich nenne, was Du zwei Spiele nennst, ein

Spiel”. |

“Why || “But why do you speak

both of physical & mental

‘strain’?” –

“Because they have a certain similarity, they have a common

element.”

What is this common element?

Can you

point to it as you pointed in …?

Can you say anything more about it than that it is the element of

strain?

¤

“It is a certain tension.” That doesn't get us any further, for why do you talk of tension in these different cases. “A certain feeling of tension accompanies || is part of both experiences”. Are you not just translating what you said before, into other language 15 or are you actually

referring to an experience like that of

feeling your heart beat. Thus I could || , as you

could say that this feeling is a

constituent both of certain sensations of fear & of

hopes || joy.

|

“But why should we call both experiences a strain if there was no

similarity between them?”

But can't the similarity just consist in this that

you feel || are inclined to use in both

cases the same metaphor, the same expression.

|

And we are not only inclined to use the phrase a deep sorrow & a

deep well but very often to accompany both by the same gestures & to

say them in the same tone of voice.

|

“There is something in common between the two

experiences only I don't know what”.

Well this too characterizes your experience &

I should say when you'll say that you know what is

in common between them your experience will be different.

|

To say that you use the same word ‘strain’ in

all the different cases because of a similarity is all right if you wish to

distinguish

16 this case from the case of the

word ‘bank’.

The river bank & the

money bank are not so called

because of any similarity.

|

“But isn't there a particular experience of

similarity which you have when you compare physical &

mental strain; just the experience you don't have when

you compare a river bank & a

money bank?”

|

But do you also experience a similarity between this similarity and

other similarities?

For what makes you call this a similarity (if you think there

always must be something to make you call a thing

what you call it).

|

Consider uses of the word ‘similar’: We say

these two pieces of paper have similar colour if it is difficult for us to

distinguish them to say which of them is darker.

Now compare the experience of difficulty to say

which is darker with that || the experience of similarity when

it is impossible not to distinguish them but when I say I like my

trousers & jacket to have similar colours so as not to have

too strong a contrast.

17 |

“Familiarity || “The

feeling of familiarity is a feeling of

at-homeness.”

|

Aren't my chairs etc. familiar to me

& do I always have a feeling of at-homeness when

I see them?

|

“But what else does it mean ‘that you are familiar with

them’?”

I am not surprised to see them; I should on being asked, say that I

see them every day, that I have sat in them

hundreds of times.

I could describe on what occasions they were used &

tell you a lot about them.

All the experiences which go along with saying

these things & the experience of doing so we can call

experiences of familiarity.

|

“Why do we call all these different experiences

experiences of strain?” –

“Because there is a common element in them all.”

|

I can imagine a case in which this kind of answer is certainly

correct: Say I call all kinds of states of excitement in which I

feel the blood rush up into my head congestional

experiences.

18 |

Now is it true that || should we say that

all the experiences of strain

have a common element?

|

‘Perhaps we had better say that they are all

similar || in some respect similar.’ |

Do you mean there must be a common element, or there actually

is one.

If the latter, what makes you say ‘there is a common element’?¤ |

There seems to be a difference between this case & that when we

say “well, we call this colour ‘red’ because it

is red.”

I.e. we seem to use the word

‘strain’ here in a derivative sense, as opposed to a

direct sense.

|

What does it consist in to use a word in a derivative

sense?

“In this that its derivative sense is not the same

but only similar to the direct one.” – |

There is something very queer in the

proposition ‘when we look at a well

known word we have a particular sensation’.

“When we pronounce the words ‘and’, ‘if’ etc. we have peculiar sensations”. 19

↓ 648“When we understand a word || an ordinary word like ‘tree’, ‘table’, we have a peculiar sensation.” “As opposed to what”. The word ‘and’ = + gives me a different sensation from the word “and” = “¤and”. |

“This face gives me a peculiar impression, the same impression

which the other one gave me.”¤

“This face & the other make me smile.” |

“These faces make a particular impression on me which I

can't describe.”

What does it mean ‘I can't

describe’?

Is there anything to describe?

What is this impossibility of describing like?

For there are many different cases.

And in one ‘I can't describe’ is really a

grammatical remark.

|

“I had a definite sensation a moment ago

20 & I have it now”. |

“I'm seeing this as a ship now, whereas I always

saw it just as a decoration

before.” –

“But what's it like to see it ‘as a

ship’”.

“I can't describe”.

“But what made you say you saw it

“ || ‘as a

ship” || ’, what made you use this

expression?” –

“I saw as it were how the sails were inflated by the

wind.” –

“But did they look as though they bulged more?”

–

“No, I just had a feeling

& these words suggested themselves for

it.”

|

When you say, you have a definite

feeling which you can't describe, is this a

peculiar experience, don't you always have a || some

definite feeling?

Isn't all you want to say something like: “I feel

very interested now.”

|

We must do with these expressions something similar as with

such expressions as “war is war!”

|

The form of the expression “I have a particular

feeling which I can't describe” is

misleading.

21

It would be just like saying “everything has a particular || peculiar character”. |

“A chair has a particular character about it.” |

Aber ist nicht ein Unterschied zwischen den Dingen die eine gewisse Wärme

um sich haben & denen die uns fremd sind? |

Man kann doch von Dingen reden die uns, sagen wir, häuslich

anmuten. |

“Jeder der geschriebenen Buchstaben hat einen eigenen

Charakter”.

Das meint man aber nicht im Gegensatz zu den gedruckten oder zu denen

einer andern Schrift. |

Vergl. “Jede

dieser Wohnungen hat einen besonderen Geruch.” |

Könnte man also Zeichen ohne Charakter & Zeichen mit Charakter

unterscheiden? 22 |

Kann ich aber darum sagen, daß die Buchstaben mir jeder

ein bestimmtes Gefühl geben?

Es könnte so sein, beim einen würde mir warm beim andern kühl, – aber

muß es so sein?

Es kann das Erlebnis des ‘bestimmten Charakters’ auch bloß damit bestehen daß man mit bestimmten Tonfall sagt “er hat einen bestimmten Charakter”. |

Das Wort als ‘Ausdruck des

Gefühls’ |

“Er legt alles Gefühl in dieses Wort”. |

Wenn man einen Gegenstand abzeichnet ist man geneigt zu

sagen: “er hat (oder die Krümmung hat) einen

ganz bestimmten Charakter”.

Und man ruft sich z.B. das Gefühl,

Erlebnis, dieses Charakters immer von neuem vor.

Das Erlebnis mag nun z.B. darin bestehen daß uns ein

Wort ein Gegenstand vor dem Geist tritt, daß wir eine bestimmte Geste, ein

bestimmtes Gesicht machen.

Aber auch daß uns nur die Worte kommen: “diese Kurve hat

nämlich einen ganz bestimmten Charakter”.

23

Und das ist eigentlich nur eine Betonung der Kurve

selbst.

D.h. es hat die Multiplizität

einer Betonung dessen was z.B. beim Sehen des

Gegenstands erlebt wird. |

Wenn man den Ausdruck || die Geste für das Gefühl sucht || findet so

findet || sucht man auch ein neues Gefühl.

Es ist nicht wie wenn man etwa nachschlägt was ‘Trauer’ auf Russisch heißt. |

“Eine erinnerungsreiche Gegend”.

Formen sind manchmal assoziationsreich.

Aber kann man den Assoziationsreichtum eingeführt nennen?

|

“Er hat das Lied ausdrucksvoll gesungen”. –

Kann man fragen “mit welchem

Ausdruck?”?

Wenn man fragte: “Worin bestand es daß er ausdrucksvoll gesungen hat”, so käme darauf etwas von der Art zur Antwort: “er hat z.B. diese Stelle … so & so gesungen & nicht, z.B., so …”. Aber diese Feststellung hat eigentlich eine ganz andere Multiplizität als die erste, denn sie ließe sich nicht auf ein anderes Lied an 24 wenden das ausdrucksvoll gesungen

wurde.

Die Erklärung könnte sein:

“ausdrucksvoll ist es wenn es so gesungen wird wie

ich es mir gesungen wünsche.” |

“Wenn man dieses Gesicht ansieht, wird einem

warm.”

Wenn man fragen würde: “wird Dir wirklich warm”,

würde er sagen “nein, nur bildlich gesprochen”.

|

“Eine warme Farbe” |

“Ist weiches Wasser nur bildlich gesprochen

‘weich’ oder im eigentlichen Sinn des

Worts?” |

Denken wir uns jemand würde statt von einem ‘rötlichen

Blau’ von einem ‘roten Blau’ sprechen &

sagen das Wort “rot” sei hier in

übertragener Bedeutung gebraucht. |

Nun glaubt man aber sagen zu können: Es kommt

einfach darauf an was Du mit dem Wort meinst; meinst Du das was

geistige Anstrengung & körperliche Anstrengung mit einander

25 gemein haben so brauchst Du das Wort in

beiden Fällen in der

eigentlichen

Bedeutung; wenn nicht dann hat es in

den beiden verschiedene Bedeutung & man kann von

direkter & übertragener reden. |

Aber was heißt es das meinen was den beiden gemeinsam ist?

(Ich kann [Beispiel gehört hierher] doch nicht

darauf zeigen.)

Heißt ‘das Gemeinsame meinen’ in

diesem || dem Fall nicht einfach ‘beides

meinen’? |

Denke, man sagte: “Man nennt das siedende

Wasser & das Blut des Menschen warm, weil ‘warm’

das heißt, was beide Wärmegrade gemeinsam haben”.

|

a) Wenn gefragt wird was haben diese Bilder gemein so zeigt

man einen Fleck mit einer Farbe die in beiden vorkommt.

b) Wenn gefragt wird was haben die beiden Farben gemein (z.B. ein rötliches blau & ein rötliches gelb) so zeigt man einen Fleck mit gelber Farbe. Hier sieht man wie verschieden man das Wort “das & das gemeinsam haben” gebrauchen kann. Und keine der beiden Arten ist direkter oder richtiger! |

Man könnte nun z.B. sagen mit

26 ‘gelblich’ meine ich was

der beiden Farben gemeinsam ist & ich tue es indem ich mir

dabei etwas gelbes vorstelle. |

“Man meint was den beiden gemeinsam ist wenn

¤man an das denkt was ihnen gemeinsam

ist” aber wie tut man das?

Wie denkt man z.B. an das was

den Buchstaben R & B gemeinsam ist.

Daran denken heißt manchmal darauf zeigen, es sich vorstellen

u.a.. |

“Denke an das was allen Pflanzen gemeinsam

ist!”. |

“Ich nenne beides eine ‘Anstrengung’, weil ich

damit das meine, was beiden gemeinsam ist”. |

Die Aufgabe die Vokale nach ihrer Dunkelheit zu ordnen ist

in vielem ganz analog einem sogenannten mathematischen Problem. |

“Warum nennst Du das ‘rot’?”

–

“Ich dachte Du nennst ‘rot’ alles was diese

Farbe gemeinsam hat”.

27

Dagegen kann man sagen: “Ich dachte Du nennst Schmetterlingsblütler alles das was so eine Blüte trägt.” Auch: “Ich dachte du nennst ‘rötlich’ alles was diesen Ton gemeinsam hat”. |

Ich meine nicht daß man den Ausdruck

“diese beiden Farben haben das → (auf eine Farbe

zeigend) gemeinsam” nicht gebrauchen kann.

Man könnte z.B. gefragt was zwei

Schattierungen von Rot mit einander gemein haben auf das reine Rot

zeigen.

Aber was das heißt muß erst in einem Sprachspiel

festgelegt || bestimmt werden.

Man könnte z.B. nun nicht fragen:

“Ist es wahr, daß sie dieses Rot mit einander gemein

haben?” |

“Warum nennst Du das

“ || ‘Schmerz” || ’?”

–

“Nun daß heißt ‘Schmerz’.”

“Warum sprichst Du von einem seelischen Schmerz?” – “Weil es wie ein Schmerz ist.” |

Sprachspiel: ‘Hell’ &

‘dunkel’ wird an Farben erklärt & verwendet. –

Dann sage ich: “Ordne die Vokale nach ihrer

Helligkeit”.

Hier würden wir von übertragener Bedeutung reden. 28 |

Philosophieren besteht darin daß einem Beispiele in der rechten

Reihenfolge einfallen. |

Denken wir uns jemand würde sagen: “Die Wörter

‘hoch’, ‘tief’ sind auf Töne in ihrer

ursprünglichen

Bedeutung angewandt; das ist auch im Fall von

‘hoch’ &

‘tief’.” |

Man || Jemand lernt die Farbwörter ‘rot’,

‘grün’ etc. für die reinen Farben

gebrauchen.

Dann zeigt man auf einen Haufen von rötlich & grünlich blauen

Stücken & sagt: “sondere die roten von den

grünen.”

War das Wort in der ursprünglichen oder in einer anderen Bedeutung

gebraucht worden.

Man könnte hier sagen: Wenn Du mir aufgetragen hättest einen roten Fleck zu malen so hätte ich nicht diese Farbe gemalt. |

In einem Fall fühlen wir, wir gebrauchen eine

Metapher, im andern Fall, wir gebrauchen das Wort in

direkter Weise. |

Worin besteht der Unterschied dieser Erlebnisse?

Wir sehen den einen Gebrauch als 29 etwas Abgeschlossenes an.

Handelt es sich hier um zwei klar getrennte Erlebnisse?

Das Erlebnis, ‘schwarz’ zu nennen, was schwarz

ist; & das, ‘schwarz’ zu nennen, was

gleichsam schwarz ist? – |

Ich könnte mir denken, daß Einer gewohnt nur von

‘körperlicher Anstrengung’ zu reden sagte:

“das Denken ist gleichsam eine Anstrengung.”.

|

Könnten wir uns aber nicht auch diesen Fall denken: Es kennte

einer die rote Farbe nur von der Gesichtsfarbe her; er wollte nun die Farbe

eines Apfels beschreiben & sagte, der Apfel sei

‘gleichsam rot’.

Wer das sagt denkt etwa an Gesichter. |

“Der Himmel ist gleichsam blau.”

|

“Das Gesicht macht einen dunkleren Eindruck obwohl die Hautfarbe

in Wirklichkeit heller ist.” |

Denke an die Menschen die, wenn sie einen angeschlagenen Ton

nachsingen sollen die Quint davon singen.

Ist die Quint nun der gleiche Ton oder

nicht?

30

|

Ich könnte mir einen Menschen denken dem man gelehrt hätte färbige

Gegenstände durch malen zu kopieren & der den Himmel

immer weiß kopierte.

D.h. ich könnte mir, irgendwie, leicht denken, daß

ich es selbst so machte.

(Indem ich sozusagen eine andere

Projektionsmethode anwende.) |

“Er hat gleichsam eine dunklere Stimme.”

–

“Warum sagst Du nicht einfach ‘er hat eine

dunklere Stimme’?

Sie ist doch dunkler”. –

“Aber dunkler nennt man ja eigentlich

diese || die Beziehung

zwischen diesen beiden Farben.

Z.B. das (zeigend) ist dunkler als

das.” –

“Ja, aber diese || seine Stimme

ist auch dunkler als die des Andern.” |

Man kann sich denken, daß ein Gesicht dunkler aussieht, als das

andere obwohl seine Hautfarbe nicht dunkler ist. |

Könnte man aber in diesem Falle umhin von zwei Arten des

Gebrauchs zu reden? 31 |

“Why do you call this ‘blue’?”

–

There is no ‘why’ to it if you're referring to

a reason. –

|

But there is also this case: “I call this blue because in

daylight it looks blue.”

But also: “I call this blue because it is almost blue”. |

“What do these two colours have in

common?” –

What sort of answer do you want?

For imagine these different games: ‒ ‒ ‒

|

The capacity of solving philosophical problems is the capacity

of remembering the right examples (in the right

order). || of calling to memory

the right examples.¤

|

“Why do you call this a

‘strain’

too?”

Because it has something in common with bodily strain. –

“What?” –

I don't know but there is obviously a similarity. |

Then when you said the two experiences had something in common this

expression just compared this case with that when one

primarily speaks of common elements between

32 two things.

(Nr.

… )

|

(If philosophy deals with its own method

how can || does it come to an end at all, how

is it bounded?

Its domain || field is

that of || circumscribed by || limited by the field

of our philosophical troubles.

It only devises remedies for mental

troubles & where such troubles actually don't

arise (as a matter of psychology) it has

nothing to say || there is no job for philosophy.)

|

It was then no explanation just to say that the similarity

consisted in the occurrence of a common element.

|

Now shall we say that you have a feeling of similarity if you compare,

say, physical & mental strain?

|

If you say you have let's hear some more about || let us

ask a few questions about this feeling.

Would you say it was located in this or in that place of your body? And when is it present? When || Perhaps you say when you compare physical & bodily strain, – but comparing is a complicated activity & do you have the same feeling throughout the whole activity? |

∣ (This face has no real expression, no meaning, it

doesn't click.) ∣

33 |

Perhaps you say: ‘Anyhow, if I have compared

& say they are similar I mean what I say & this too is some

sort of mental event & perhaps the feeling of similarity is the

feeling you have while you say the word ‘similar’

meaning it.’

|

Pronounce the word ‘similar’ in a sentence very

slowly meaning it & see if you really have one feeling

accompanying it from beginning to end.

But surely it is a different experience if I say similar

& mean it & if on the other hand I say it without meaning

it.

|

It is no more true that you have one peculiar feeling corresponding to the

meaning of ‘similar’ as it would be to say that you have

one peculiar facial expression when you say it.

Although on the other hand there will probably be one

particular facial expression || some particular facial expressions

with which you often say the word but you won't always have it

when you say (& mean) the word || the word

(meaning what you say) & the same facial expression

will accompany other words & phrases too.

34

|

It is often useful for us to speak about gestures

& || , facial expressions & the like

instead of of the experiences bound up with them.

|

Beispiel von dem der auf den Befehl Dinge ihrer

Dunkelheit nach zu ordnen auch die Vokale

ordnet. |

Ton des Befehles ordne die Töne nach ihrer Dunkelheit &

gewöhnlicher Ton. |

Man ist versucht zu sagen er muß etwas anderes unter

‘dunkel’ verstanden haben.

Vergleich mit einem anderen Instrument nach dessen Ablesungen er alles ordnet. Aber ein solches Instrument ist nicht vorhanden. Es muß vorhanden sein, heißt daß wir entschlossen sind dieses Bild zu gebrauchen. |

“Aber es ist doch gewiß ein anderer Sinn von dunkel den

wir hier gebrauchen.” Was soll das heißen? Unterscheidest 35 Du hier den Sinn von Gebrauch &

willst sagen daß wenn einer das Wort so gebraucht daraus folge, daß auch

anderswo etwas anderes vorsichgehen müsse, oder werde. –

Oder willst Du nur sagen dieser Gebrauch sei doch ein anderer als

jener? |

Bist Du nun zufrieden wenn ich die Unterschiede in den

beiden Fällen aufzähle.

Oder muß ich noch etwas anderes

zugeben || zugestehen. |

Wie, wenn jemand sagte: “das sind doch verschiedene Arten

des Gebrauchs von ‘rot’”.

Ich würde sagen das eine ist hellrot das andere dunkelrot, aber

warum soll || muß ich das verschiedene Arten des

Gebrauchs von ‘rot’ nennen? |

Aber besteht die Verschiedenheit || Andersartigkeit des

Gebrauchs noch in etwas Anderem als in den Verschiedenheiten die

wir aufzählen können?

Denn gewiß in einem Fall lege ich etwa farbige Flecke zusammen &

vergleiche sie indem ich bald den einen bald den andern ansehe, ich halte

sie vielleicht in ein besseres Licht; ich male eine Farbe die heller ist als

eine andere u.s.f.

u.s.f.

Im

36 Falle der Vokale fand

kein solches zusammenlegen, malen etc. statt. |

Aber ich sehe doch daß die Relation zwischen einem helleren

& einem dunkleren Stück Stoff eine andere ist als zwischen

dem e & dem u.

Wie ich anderseits sehe daß die Relation zwischen u &

e die selbe ist wie die zwischen e & i. |

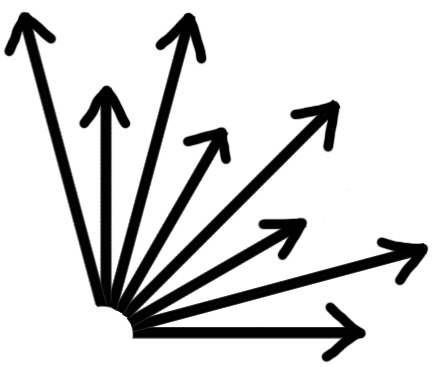

Ob Du die Relationen dieselben oder verschiedene nennt, das hängt wohl

davon ab, wie Du sie vergleichst.

Ist → dieselbe Richtung wie ← oder sind sie entgegengesetzt. Spiegel Entsprechende Umstände können uns veranlassen zu sagen die Relationen sind verschieden, andere, sie seien die gleichen. |

Es ist hier wie mit der Fortsetzung einer Reihe.

Intuitionismus.

|

“It isn't only that you use the word ‘red’ for this

colour but you use it with a particular

experience.”

37

“Experience when we use a word in a derivative sense.” Tone of voice in the order “now arrange the vowels in order of their darkness”. |

The tone of voice may be, all things being equal, the decisive

experience?

|

He said & meant it sounds as

though two activities here ran

parallel.

|

But surely there is a difference between saying something

& meaning it, & saying it without meaning it.

There needn't be a difference while he says it

& if there is a difference then this may be of all

sorts of different kinds according to the surrounding

circumstances.

It does not follow from the fact that there is what we call a friendly & an unfriendly expression of the eye that there must be a difference between the eyes of a friendly & of an unfriendly face. 38 |

Suppose one said: “this line can't make the face

look friendly as it could be belied by other lines.”

|

Under these circumstances we call this activity reading.

If he does it we say he is reading & if we order him to read

& he does it we are satisfied.

Under these circumstances we call this picture of his eye a friendly eye. Under these circumstances this was what saying & meaning it consisted in. |

In a large group of cases believing something is the same or something

very similar to uttering || expressing your

belief.

|

All the circumstances which

make believing intersect in the present moment.

|

Now is he meaning it when he says it or isn't he?

39

|

“I said it & meant it.” –

How did you do it? –

|

Compare meaning: “I shall be delighted to see

you” with meaning “the train goes at

3˙30”.

|

There are certain mental

events || experiences || expressions

characteristic of

believing i.e. there is a large group of cases in

which they together with other factors constitute what we call

believing.

But because ¤

these first components aren't present in all

cases of believing you mustn't conclude that any of the

others is.

|

Comparing || Compare lying about the train with lying about being

delighted.

|

It is even possible while lying feeling quite strongly

what is usually felt when one means sincerely what one says.

|

And at the same time one just refers to || refers to just these feelings

sometimes when one says I said it and meant

it.

I.e. one would

mention these feelings as characteristic

40 for one's meaning what

one said.

And if anyone said “But these same feelings could

also have been present if you hadn't meant it” one could

answer: “not in the kind of case this was”. |

“He was very friendly, he smiled at me

most kindly”. –

But he might have done that & felt unfriendly.

|

“This is a friendly face, look at the

eyes.” –

But these same eyes would not be friendly in another face.

“Still in this face they are friendly”.

|

Should we say “under these circumstances I

call this reading” or “under these circumstances I regard

this as carrying out my order read” etc.? |

One remembers just that feeling when one says I meant

what one said, although etc..

This feeling then stood out, it is a question just whether one had it or

not.

And those circumstances which would || could

have contradicted this feeling don't come here at

all into question.

41

I would perhaps ◇◇◇ be ready to say in this case that I meant by ‘I meant it’ I had this feeling. |

And there are cases where I would be ready to give such an

explanation of ‘I meant’ & cases like that

of ‘the train leaves at 3˙30’ where I

might say “well I just said it, why shouldn't I

have meant it”.

|

We very often find it impossible to think without

speaking to ourselves half aloud; – & nobody

asked to describe what

happened in this case would ever say that something, the thinking,

accompanied the speaking were they not

tempted || seduced to do so by the existence of

the two verbs speaking & thinking

& their use in many of our

common phrases.

If anything can be said to accompany || go with the speech it would be something like the modulation of vocal means of expression. But does the Ausdruck accompany the words in the sense in which a melody accompanies them? 42 |

Wir zählen nur eine Verwandtschaft

zwischen der Dunkelheit der Farbe & der Laute.

|

If || One thing is important if you say when I say “blue” I have a particular experience, the word comes in a particular way you don't trouble to think of (the) many different experiences while saying the word ‘blue’ & the word ‘three’. |

¤

|

Das gleiche Bild kann Vorstellung von Verschiedenem sein.

Die Umgebungen sind verschieden.

Der Gebrauch, die Atmosphäre. |

But moreover, the difference between observing & acting

does not at all necessarily consist in a difference in every moment or phase

of the action.

Exactly the same may happen during the action

43 but the surroundings will be

different.

Moving in different circles.

Different atmosphere.

|

Es denkt |

Absence of the experience of saying “Oh

that's where it's going

now”.

|

“Of course we aren't surprised as we do it

ourselves!”

We take as the criterion of doing it ourselves the absence of surprise. |

One might think the absence of surprise comes from knowing

beforehand what one is going to do.

|

Involuntary speech

“Stop!”,

“Oh”, “Help!”

Like blinking one's eyelids or raising a hand for protecting || to protect the || one's face. |

∣ Speaking as somebody's friend,

doctor, speaking as a private person, as a university

lecturer|.

One might think that whenever a man speaks he speaks as

someone. ∣

44 |

Is moving one's fingers in example № … involuntary should we call it so? Is breathing voluntary? |

Should we say that when we shout

“Help!” there is no act of volition, whereas

when we say “Hallo!” to a friend there

is?

|

Compare the cases when you raise your hand with an effort

or move it without effort in a particular curve (say writing a letter in the air) or after deliberating whether you lift it or not, you ‘find yourself lifting it’. |

Ordinary speaking is called voluntary not because there is a

particular effort present, the act of will. |

Premeditated acts 45 |

If against my will I shriek with pain

that || the

overcoming of my will is not like the overcoming of a muscular

effort.

|

One might say “surely shrieking with pain is a good

example of involuntary speaking because here ¤ far from

there being an act of volition which worked the speaking || not only

there is no act of volition by which we speak

there even was one against it.”

I should say: Certainly I too

would || should call this

involuntary speaking.

But the effort is also absent in most cases of voluntary

speaking.

And I agree that an act of volition preparatory to or

accompanying the speech is absent if by ‘act of

volition’ you refer to certain acts of intention,

premeditation or effort.

But then in many cases

of voluntary speech I don't feel an

effort, many were not premeditated

& as to intentions sometimes the unintentional

action is characterized as such by an experience of surprise in others the

intentional is characterized by a spoken or imagined expression of

intention.

46

|

“All that happens is that I get out of bed”.

“All that happens when I mean it is in this case that I say it”. That is to say: I don't call it ‘meaning what I say’ because of any peculiar experience which I have while I say it. But what is a peculiar experience? Isn't the absence of an experience an experience? Yes but we don't call the absence of a feeling a feeling or the absence of pain a pain. It is certainly sometimes misleading to say: “Not the presence of something characterizes this case but the absence of something”. But when we are inclined to look out for a sensation it makes sense to point out that in such & such a case we don't find a peculiar sensation but we do in the opposite case. |

In a great many cases the difference is not one lying in the

action or an accompaniment of it, but in the

surrounding circumstances the environment of the action.

47 |

It is as though I said “these two people move in different

circles” does not mean that they are never surrounded by exactly

the same people, e.g. when they walk in the

street.

|

A kind & an unkind expression might look exactly alike only what

goes before & after as || may be different. |

Our tendency is to describe something that is a matter of atmosphere

round a situation in a too primitive way as a

difference in the situation.

|

Thus one says: “something peculiar happens when the name of

a colour comes, something different when the numeral

comes.”

But we have no reason at all to say this.

But I agree that the surroundings of these two are

different.

|

Why do you say “something does happen when I understand

a word!”.

Do you remember that the same thing always happens or do you know that one

of, say, four

48 things happen?“Es drückt etwas aus. Es sagt mir etwas.” |

One face reminds you of someone, one strikes you as Chinese, one makes you

think of an illustration you have seen.

|

I'm seeing this as a face as opposed to seeing it as a

wineglass in a round hole.

And when you change over from the one to the other you change the ‘attention’ & you look at it with a different face. |

Look at W, alternately as a

W

and as an M

upside down.

How queer that you can comply with this order.

And what do you do to comply with it?

49

“I see it resting on the upper

end”.

But what does that mean?

Aren't there lots of possibilities? &

isn't one of them that you read it

M

instead of W?

|

Do I get all sorts of impressions from these figures and all

along see them as faces?

|

And how about a real face, – does one see that too as a face

always?

Is it correct to say that if we don't see it as something else we have one particular attitude towards it? And don't (or do) you look in a particular way at everything you look at? Or: couldn't you look at everything in several ways? Look at your tea kettle & see its spout as a nose. – |

Do you wish to say this soap has a particular smell as

opposed to no particular smell; or that it has this smell as opposed to

another one or both the first & the second. |

We are tempted to ask: “What does seeing something as

a face consist 50 in?”

And we feel tempted to ask: “does it consist in anything obviously superadded to the mere seeing of the strokes, or is there only a ‘seeing it as a face’ as distinguished from seeing it as something else?” |

Are we aware of seeing a table which we see

‘as table’?

|

Suppose I said “I am in a particular bodily position

now”; What happens is that I am concentrating my

attention on the particular sensations I have in

this situation.

|

Ich sehe auf an einem Kleiderhaken einen Rock & eine Kappe

aufgehangen, sie machen mir – bin ich versucht zu sagen

– gleich einen ganz bestimmten Eindruck.

Aber vergleichen wir den Eindruck eines Pelzrockes

mit dem einer Regenhaut, eines neuen glatten Rockes & eines alten

schäbigen.

Ein Hals macht einen andern Eindruck als ein Gesicht & einen

anderen machen Füße.

Aber diese Eindrücke erhält

51 man nicht immer wenn man diese Dinge

sieht.

Kann man dagegen

nicht sagen, || : wie ich den Rock gesehen habe,

habe ich ihn sofort als Rock gesehen, noch ehe ich irgend

einen besonderen Eindruck, etwa der Wärme oder Weichheit hatte?

|

Aber bist Du sicher daß Du eben nicht bloß diese bestimmte Form des

Rockes, gesehen hast, – || , – &

freilich nicht mit Staunen, nicht mit der Frage “was

ist das?” u. dergl.? |

The answer to the question “how does he enter the

room?” might in this case be a picture showing him entering

the room.

|

“The word ‘red’” – we are

inclined to say – “comes in a particular way, namely in

this way.”

But “in this way” here

only means: he comes in the way he || it comes in the

way it comes.

|

It is as though calling it a particular feeling when one sees red

still had || makes sense although the feeling was

to be bound up with seeing red.

|

We use the word “particular” here as an emphasis whereas

it seems that

52 we use it transitively &, in

particular, reflexively.

|

You think you compare it with a paradigm & it agrees or it

fits into a mould ready for it in your mind.

But in your experience no such mould or

comparison enters there is only this shape not any other to

compare it with & you, as it were, say “of course”

to

it. But || (but not because it fits anything,

but because of no reason¤).

|

You lay || You are laying an emphasis on it but

you express this in a form which tempts you to believe

that || makes it seem that you are recognizing

it.

|

Instead of saying “it comes with a particular

experience” you should have said: “I concentrate my

attention on the way it comes or on its coming” (compare

‘I draw the way he comes into the room’). |

The word in this case comes with a particular experience should in this

case mean ‘it always comes

53 with the same experience’, but you

aren't ready to confirm that!

So why are you tempted here to use the phrase while

contemplating the way it comes?

Because you are contemplating it.

You thereby lay an emphasis on it. |

If you try to see what it is you are comparing it with you should be

inclined to say that you compare it with itself.

And this is a most characteristic situation. |

The way can't in this case be separated from

him.

|

Now if I wished to draw him coming in & was

contemplating his coming in I should while doing so be inclined to say to

myself & repeat: “He has a particular way

of coming in”.

But the answer to the question “What is this

way?” would be “it's this

way” (perhaps drawing it).

But there may be no such answer & my phrase may

54 only mean: “I contemplate his

position”.

Our expression on the other hand made it appear as though his position was not characterized by anything but itself. |

We very often use the reflexive form when we wish to emphasize || lay an

emphasis on something & its meaning & such

expressions can then always be straightened out: Thus we say a

man's a man

À la guerre comme, à la guerre. If I can't I can't. || , I am what I am. That's that. Take it or leave it. It either rains or it doesn't rain. This is no piece of information; if it rains we shall ‒ ‒ ‒ There must be a greatest number of examples let it be 500. |

“If the length of the one is L the length of the

other is L”.

This is a form of various

propositions but not itself a

proposition

But we could say: “If instead of

‘length’ we put ‘L’ || Let

us put ‘L’ instead of

‘length’: then they have the same

L.

But it makes sense to say: “Let us consider propositions of the form “if A has the length L so has B”.” 55 |

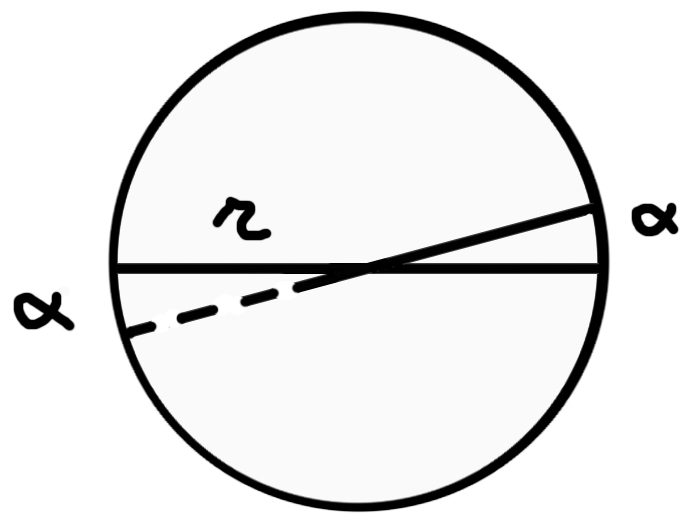

“Denken wir daß der Radius r zwei Verlängerungen

habe”; – aber das ist ja wirklich möglich!

Wir machen keine absurde Annahme. |

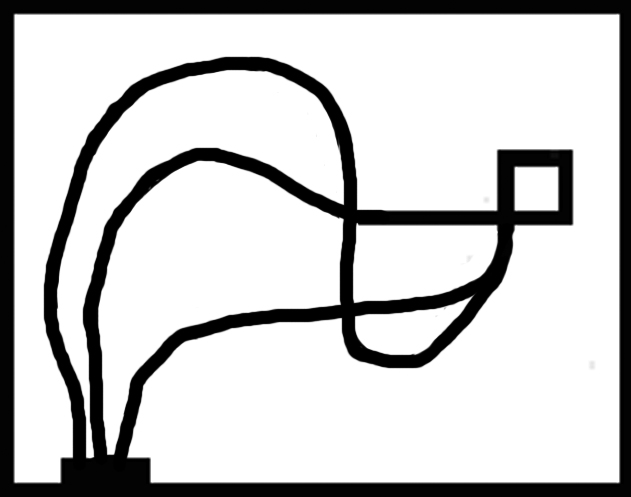

Stelle Dir diesen indirekten Beweis so vor daß das was bewiesen wird nicht

offenbar zu Tage tritt sondern durch eine Kette von

Transformationen versteckt ist; & ich zeige dann daß wenn

dort ↗ ein Spalt klafft auch da

↙ einer sein muß.

Man denke sich einen komplizierten Mechanismus der

zwischen zwei Stellungen vermittelt. |

Der Beweis zeigt die Inkonvenienz der

Fortsetzung daß der Radius zwei Fortsetzungen haben kann.

Der Widerspruch den der Beweis ergibt ist harmlos. |

Aber die Annahme erscheint auf

56 den ersten Blick absurd.

Aber wenn sie wirklich absurd ist dann kann man sie nicht

machen. |

“This face has a particular

expression?”

I'm inclined to say this when I'm letting it make its full impression on me. And this is something like letting it govern you (sich ihm hingeben). It is then as though I wished to say what this expression consisted in & really this is what one does when one wants to find the right expression. |

The question “What expression

does it have here” means, I wish to get its full

impression.

|

“But surely, this face has a peculiar

expression!”

What does this mean?

57

Has it got something?

Isn't it something?

|

It would be interesting to imagine beings which consisted

of nothing else than a circular stroke

& two eye strokes &

nose-stroke & one mouth-stroke

& whose movements consisted of || in

movements, changes of the shape of these strokes.

|

Ich hebe es hervor!

Es ist als machte ich eine Stampiglie davon. |

Philosophizing is an illness & we are trying to

describe minutely its symptoms,

clinical appearance. |

“It couldn't be just these strokes!

You're obviously comparing them with something else you

know.

There is something behind those strokes!”

|

To say ‘it has the expression’ makes it appear

as though I could separate the expression from the face.

|

“You won't tell me that this tune doesn't

express something particular”.

58

Does this mean that you make particular movements to it? But particular movements as opposed to which? |

“But these movements also express

something, they aren't just

movements!”

|

Supposing you said: “You won't tell me that

this tune hasn't a particular rhythm”! –

“Why, of course it has a particular rhythm, which tune

hasn't.”

It here seems as though the peculiarity must consist in our recognizing it as this rhythm which we know from somewhere else. But this may be a delusion & it has just its own rhythm but a rhythm which strikes you, say makes you sway. |

“It says something” could in this case be translated

into “it speaks to me”.

59 |

Als müßte ich diesen Ausdruck (des Gesichts) noch irgendwo anders

wiederfinden! |

Eine Zahl als Jahreszahl sehen. |

There are experiences of familiarity. |

“This is a serious face”. –

What is it that is serious?

|

Does it mean that it makes me serious, that it has such

& such an effect on me?

And if eating a soup has this effect do I call it serious? And can't a smiling face somehow make me feel serious? |

On the other hand: does a ‘serious face’

60 always strike me as serious? |

But can't a chair look serious?

“But not in the sense in which a face

does”. –

What does this mean?

|

If looking at it so that you get its expression consists in

imitating it, what has the expression, the face or

me?

Is it the face insofar as it has a certain effect?

What is heavy the balance or the weight? |

How can I be sure that lengthening the mouth is what makes it look

serious?

Are any experiments needed for that?

|

Do I see it by introspection?

Is

61 it self-evident?

|

Isn't it that I measure the picture by a different kind of

instrument; weigh it on a different kind of balance. |

Does Harmony treat of our feelings?

Is it psychology?

|

Is it a delusion consisting in

“projecting” our own feelings into the

thing we see?

Is there such a case of projecting?

Where do we take this idea from?

|

Is the sugar sweet, or do we project the

feeling of sweetness into the sugar?

|

Es ist als wäre jede Art & Weise des Lebens etwas was beim Sehen

gegenwärtig ist.

Als wäre jeder mögliche Kontrast eine Färbung.

Als hätten wir zuerst das offenbar reine Sehen & dann

träten verschiedene andere Erfahrungen hinzu. |

Es ist als bestünde der Eindruck eines

62 Gesichts aus so & so vielen Teilen,

dem rein Optischen, dem Gesichtsausdruck etc..

|

“A word (particularly a well known one) has”, we

should like to say, “a particular expression (facial

expression).

We don't just see it

we feel something – or all sorts of things – when we see

it.”

This is almost as if one said “if I see red I have all sorts of feelings, the feeling of the absence of green, of blue, of yellow, etc. etc.”. |

It is as though we saw a face first purely visual then in

addition to that as a face then in addition to that as a

Chinese face & in addition to that as a well known

one.

|

Now we can imagine additional processes

corresponding to each such case but these are not ‘directly

perceived’.

|

The word ‘that’ has a peculiar expression.

What do you contrast it with?

Can you …

63

|

Would you think about it as you do, if you did not know something about

the optical apparatus of our eyes?

|

It is as though I had necessarily got to say that I distinguish

elements in the seeing of a face or a word.

|

Should I say “This eye sparkles” or that

I, as it were, sparkle when looking at it.

Should I say that the lines of the drawn cube recede or that, as it were, I recede when looking at them? Should I say “this aspect sparkles” or “This drawing seems to sparkle in this aspect”? |

Die Wörter sind wohlbekannt; worin besteht ihre

Wohlbekanntheit? |

↘668 If I look at the word ‘this’, e.g., it looks well known || familiar to me, it looks at me with a familiar face, like an old acquaintance. – But does it always? Am I always touched when I see it? Do I remember having seen it before. Did you say to it “Oh, that's the 64 word …”?

|

You are looking at this ‘as a face’!

As what are you looking at it?

Can you show me that as what you are looking at it?

|

Seeing the word ‘That’ gives me the feeling of

familiarity whereas seeing the word ‘continuity’

doesn't give it to me.

But does the first word always give me that feeling? |

Look at a word & let it seem familiar.

Then look at one of its letters & ask yourself whether that also

seemed familiar (gave you the feeling of familiarity) when the

word as a whole did.

And on the other hand the letter is, of course, familiar too. |

p ⊃ p = T

(p ⊃ p) ∙ q =

q

T ∙ p = p p ⌵ T = T p ∙ q . ⊃ . p = T (p ∙ q ⊃ p) ∙ r = r (p ∙ q) ∙ p = p ∙ q 65

(p ∙ q) ⌵ p = p p ∙ q = p p ⌵ q = (p ∙ q) ⌵ p = p ~p ⌵ q ~(p ∙ q) ⌵ p = T(Ƒ) p ⊃ p ⌵ q (~(p ∙ q) ⌵ p) ⌵ (p ∙ q) = p ∙ q P. ⊃ .Q = T(Ƒ) ⊢(p ⊃ q) = p ~p = ~p ∙ q = ~p ∙ ~q = ~p ⊢p ~p ⌵ q = ~(p ∙ q) ⌵ q = p ∙ q ⊃ q ⊢q ~(~p ∙ ~)q = ~p p ⌵ q = ~p q . ⊃ . p ⌵ q = Log. |

Where a logical proposition has a main

. ⊃ . we may infer

the right hand side from the left.

|

~~p = p

Can we deduce this?

|

p ⌵ q

= q |

(Ƒ)

q. ⊃ . p ⌵ q

= ~q

. ⊃ . p ⌵ ~q

66 |

5

When I read a line of a writing in a well known language

trying to see what reading consists in I get a particular experience

which I take to be the experience

of reading.

|

This experience doesn't simply seem to consist in seeing

& pronouncing but in some other, as it were, some

kind of intimate

experience || experience of

intimacy.

We are on an intimate ‘footing’ with the words. |

The spoken words we are inclined to say come in a particular

way & in fact they || the written

ones themselves don't appear just like any

scratches.

And at the same time I seem unable to get hold of that

‘way’.

The process || phenomena of reading out the word

seems we¤ are

inclined to

say¤,

surrounded || enshrouded by a particular

atmosphere.

But here again I don't mean to say that I recognize this atmosphere rather I notice it when in philosophizing I read a line. And here again it is as though I didn't notice it & did notice it. |

It is the atmosphere of contemplation which I provide.

And of course I see what I see.

67

Look at a written word, say ‘read’. It isn't just a scribble it's ‘read’. I should like to say it has no definite physiognomy. But what is it that I really am saying about it?! What's this statement, straightened out?! It falls I am || one is tempted to explain, into a mould of my mind language prepared for it. But as I can't see any such mould; this simile must mean that my experience is one of putting something into a mould when I don't see the mould but just feel it. |

What do we contrast all the different experiences of familiarity

with?

|

Experience of familiarity added? It is misleading || dangerous to say that the experience of seeing a face is a compound one. |

“This word now somehow looks queer to me”.

68 |

We wish to say “it's that other thing”,

& yet …

|

It looks at me & I wish to say “it looks at me in

this way”!

|

I can't say “I see this as

this face” but “I see this as a

face”. |

Woher aber die starke Versuchung? |

“This isn't just a scribble, but

it's this particular face.” |

I am tempted to say “I don't see this as

a face, I see it as this face!”

…

|

Suppose I said “I see this scribble like

this”, – this would mean something like:

What at one time appears to me like this, at another appeared to me

like that. ⇒ |

My language || What I say predicates

something but I don't really wish to predicate anything, I

don't want to say I

69 look at this in such & such a way

which can be described without reference to this. |

In fact I don't want to say anything about

it but I want to say something to it.

|

Why do I say what I say?

What do I contrast the word with of which I say it has a

particular essence?

Or don't I contrast it with anything?

because || For that shows me what game

I'm playing with it.

For, what is the use of this phrase?

Do I say it of everything I see or only of certain shapes or of anyone

when I contemplate it in some special way?

70

|

The word … isn't just scribble,

it's this.

(And if I say ‘this’, I let the word make an

impression on me, look at it in a peculiar way.)

|

Now when I say there is particular atmosphere about my reading a sentence

what do I contrast it with?

What is it that I notice?

Am I noticing that there is the same tone throughout or one tone as opposed to another tone? Do I oppose the experience to seeing some scribbles & saying words as they come into my mind looking at the scribbles in turn? |

Now it is very easy to describe differences in || between these two cases but difficult if

possible at all to specify differences

between what is happening in the moment of saying the

words.

|

Ich kenne

mich in dem Zeichen nicht aus. I don't know this sign properly, the other I know.

What is the difference while I look at them.

71 |

“I notice that the same thing happens

throughout.” –

What, seeing words || scribbles & speaking? –

“Not that alone there is something else

something particular about the way it's

done.

I don't know what it is but there is something

happening?

Alright, but let us see what it signifies that you don't know what happens & still know that something particular goes on. For are you looking for that which really happens? Have you a method of finding it? Are you attempting an analysis? And what are your means of analysing? If not, let us look at the actual state of affairs. We have just to take this as the description of this state of affairs that you notice something going on & don't know || can't say what it is. || what.¤ |

For the word || expression that the words came in

a particular way was misleading.

You don't even know what kind of thing the word

“way” alludes to.

It doesn't for instance allude to a

process of deriving the spoken word.

If anything

72 one might use it as opposed to other ways

for instance that of thinking of any spoken word to

associate with the written one.

Or the way is a lack of any.

|

If you say you know that something goes on, are

you ever clear that

that || this something

might not be the absence of anything?

Perhaps a certain smoothness. Again the familiar look of the words. |

But nothing of what we can enumerate is anything that you should care to

call the process of reading.

|

Do you notice anything?

Don't you just direct your attention on

your reading.

You look at how you are reading, but …

73

|

Beobachte die spezielle Beleuchtung die jetzt gerade in Deinem Zimmer ist,

merkst Du sie??

“Beobachte die bestimmte Farbe Deiner Wand!”

Ja wie

solle || soll ich es || was soll ich denn

tun?

Soll ich nur in bestimmter intensiver Weise auf die

Wand schauen?

Oder nur dabei etwas sagen??? “Look at the difference between the colour of the chair & the colour of the wall!” Well what about it? “Look at the peculiar character of this writing!” |

‘Don't I notice something when

I observe myself reading?’

But what could you notice?! |

“Notice this peculiar contrast of colours!”

But what about it?

|

With what sense am I to notice the way the word comes when I'm

reading?

|

Aber kann ich nicht das bestimmte

Körpergefühl was ich jetzt habe

mit einem Namen belegen, es bemerken?

Was heißt das?

Heißt es bemerken daß ich

74 eines habe oder daß es das ist

welches …

Oder? |

Es gibt in der Musik so etwas wie eine eindrucksvolle

Phrase & wenn man so eine hört, mag man sagen: “diese

Phrase drückt doch etwas aus!”

⋎ Nur will man aber sagen: sie ist nicht bloß eindrucksvoll, sondern sie drückt auch etwas bestimmtes aus. Aber wir sagten ja, sie sei eindrucksvoll. |

“It all happens in a peculiar way.”

|

“It makes a strong impression on me.”

“It impresses itself on me”.

|

alsigon

|

“It all happens in the way A.”

|

Die “Art” ist wie eine bestimmte

Färbung.

Aber das Merkwürdige ist daß ich in dieser Färbung

scheinbar nicht im Gegensatz zu irgend einer anderen rede.

|

Now if I observe myself saying it I find

that I have to read a

75 longish sentence.

And I wish to say “it's all the same

colour”.

But it hasn't just got || I don't just notice that it has all the same colour but one particular colour! Yes, but you mistake the function of language! It seems you wish to specify it, but without pointing to it || saying anything about it || not || you don't wish to say anything about it, & it seems to you as if pointing to it specified it as though you could explain it by itself. It is as though what I pointed to was at the same time the sample & what one compares it with. |

You can, of course, take an || the reading of

an English sentence as a sample for

reading.

But taking it as a sample doesn't say anything about the

sample.

You can then say something by means of the sample.

|

In saying this wall has all one particular colour we make the same mistake

one makes thinking that if we give a || an ostensive definition we say

something about the object we point to.

|

This is a particular shape (colour) because I make a

particular face if || when looking at

it.

|

Als was funktioniert das Gesicht, die Farbe etc. worauf

ich schaue?

Als Muster oder als das worüber ich aussage? 76 |

“Bei diesem Thema mache ich eine ganz bestimmte

Geste”. |

Obwohl wir die ‘bestimmte’ Beleuchtung eigentlich

keiner anderer entgegenstellen wollen, so gebrauchen wir doch diesen

Ausdruck in demjenigen Fall, im welchen die Beleuchtung auf uns

einen Eindruck macht. –

Und das ist eine Bestimmung die unabhängig von der

bestimmten || besonderen Beleuchtung ist –,

& wir können den Eindruck auch beschreiben,

anderen Eindrücken entgegenstellen. |

It is absurd to say “you can't use negation this

way” as the use determines whether it's

negation¤.

What is to determine whether it is negation or not. 77

|

x = y,

x = x

2 + 2 = 4 Is this the result of a calculation or isn't it. If not it is a definition & how could this be a tautology? |

(∃x,y)φx ∙ x = y

. ≡ .

φx ∙ φy

|

But can't I say that I see now, – what I do see? |

When I said, I … , I wished to say that I didn't

just see anything, nor did I wish to give any general

characteristic of what I saw but ‒ ‒ ‒.

|

“Write a sentence! –

While you write do you feel something?” –

“Yes, I have a particular feeling” while

writing”.

I don't want to say just that I have the same feeling the whole time but also that I have this particular feeling. But what is this particular feeling characterized by except itself? |

The word ‘particular feeling’ belongs together with the feeling

itself.

One could just say “I have … while writing”. And during ‘ … ’ produce the feeling. |

“Observe the feeling which you have while

writing.”

79 |

It seems it has sense to say “I have this feeling while

writing”.

And while saying this I produce a feeling.

|

“Surely I can say that I have this feeling while

I'm writing”.

Of course you can say it & when you say “this

feeling” you concentrate on the feeling (which is comparable to

looking not to seeing).

But what do you do with the sentence?

What use is it to you?

|

“Observe the feeling” can't mean

“feel it”.

I can say look closely at what you see, not see clearly what you

see.

|

I can't visually point to what I see because I see the

pointing finger & it does not point to what I see but is part of

it.

|

It is as though I could say: My act of concentrating the

attention is an inward (act of)

pointing.

An act which nobody else sees but that

doesn't matter.

But I don't point to the feeling

80 by attending to it but rather produce

it.

|

“Beim Lesen eines Satzes fühl ich

einen bestimmten Vorgang.”

Was ist daran wahr? |

Wenn ich wohlbekannte Dinge sehen

habe ich eine bestimmte Erfahrung;

was ist daran wahr? |

“I notice that the wall has this particular

colour”.

|

“Do you only notice that it has the same colour throughout or do

you also notice the particular colour it

has?”

This might mean: are you impressed by the particular colour it has. |

“I know what colour it has because I see

it”.

Well, what colour has it.

“I know which colour it has.” “I know the colour.” |

It has a particular colour A & I

81 know A.

|

Ich wäge einen Geschmack auf der Zunge. |

You misunderstand the function of

language.

It seems to you as though you could say: I notice the

colour besides seeing that it has all one colour. |

You think it makes sense to say: the colour of

this→ is

this→.

|

Observe your || the feeling of writing.

“Yes I'm looking at it”, or “yes

I'm impressing it on my mind”.

|

If I observe the peculiar || particular

lighting etc. I don't do anything with

it.

|

“I see this”.

Surely it makes sense to say what I see & how could I do this

better than by letting what I see speak for itself.

But I can't point visually to what I see. ‒ ‒ ‒¤ It seems as though I singled something out but the sample can't single out itself. 82

When I said you mistake the function of language it was because a sentence seemed to you to do what only the sample itself does. The sample seemed to be its own description. |

“The wall has now got this colour”.

Imagine someone asked “Has it really this colour now?” |

Observe the lighting …. –

Hasn't it one particular lighting?

Like doesn't the sentence read give me one

particular impression?

Observe the particular thing that takes place when you read. Impress the lighting of the room on you. Suppose someone said “I am now observing the particular lighting it has”. This would sound as if he could point out which it was. |

… because by its help you seem to be pointing

83 out to yourself what colour you

see.

|

You are ordered || This tells you to concentrate your

attention on the sample and I could in fact have said “look at the

colour

of this sample”.

But this would have asked you to

concentrate on || to attend to it in a particular

way, not to attend to a particular thing.

|

By attending, looking you produce the impression.

You can't look at the impression.

|

Nothing yet is done with this sample.

|

But you might think || it might seem to you that you can look

at the particular lighting of this

room.

As though you didn't look at the room but at something else

which the room had.

And you are then in fact concentrating your attention … on the

lighting which doesn't mean to look at a

particular thing but in a

particular way.

84

(I must try to cheat myself to believe that I can look at the particular lighting of this room.) |

It doesn't say anything about the appearance of the

room.

(Rather) the appearance of the

room is the sample.

|

Observe … is like saying get hold of it whereas it

is obeyed by putting myself into a certain state. |

This ◇◇◇ a particular

lighting, get hold of it. |

The order could have been “see what lighting the room

has”.

|

“There is a particular lighting, I must

observe”.

85

|

⍈

It seemed that I could say: Now I've

noticed it something particular happens

when I read || in reading.

|

You read put yourself into the ⋎ state of attention

& say: “Something peculiar happens

undoubtedly”.

You are inclined to go on “There is a certain

smoothness about it.”

But you feel that this is only an inadequate description &

that the experience can only describe || stand for

itself.

|

“Something peculiar

happens

undoubtedly” is like saying

“I've had an experience!”

But you don't wish to make a general statement independent

of the particular experience you have had but rather a statement into which

this particular experience enters.

¥ |

You are under a particular impression. || an

impression.

|

You are saying something general & at the same time

concentrating your attention on a sample & so it seems as though

this sample entered your statement.

86

It is as though you looked into a microscope say observing the motions of animals & said to a pupil: “Something peculiar goes on there”; intending to let him look too & to use what you observe as a sample for further consideration. |

You think you've noticed the process of reading, the particular

way in which signs are transformed into sounds.

You've seen the particular process of

transformation.

|

“This sentence is spoken in a particular

tone.” –

Every sentence is spoken in a particular tone, only what makes

you say that it's spoken in a particular tone is that

you're concentrating on this tone. |

You are under an impression.

That's why you say what you say.

But the sentence that you are under an impression, is a general statement. You wish to make this impression a sample drawing a circle round it. And this action of saying something to it you mistake for saying some 87 thing about it. |

You are under an impression.

This makes you say “I am under a

particular impression.

And this sentence seems || it seems to say to yourself

under what impression you are || at least that you have told

yourself under what impression you

are.

As though you had pointed to a picture ready in your mind & said this is it. Whereas you have only pointed to your impression. You did something like drawing a circle round the colour … |

“That's how one reads!” You seem to have observed reading as under a magnifying glass & discovered || seen the reading process (which had escaped the ◇◇◇ || naked eye || careless || superficial observation.) But the case is more like that of observing something through a coloured glass. |

You interpret your impression || You are under an impression which you

interpret || & you interpret this as

one of having noticed something which was independent of the

particular signs you saw, the words you uttered, the writing

etc.

88 |

Thought expressed by architecture.

|

Stiefmütterchen, “jede Farbenzusammenstellung sagt

etwas, speaks to me”.

Everyone of these men says something. |

“That's what happens when I read (at least

what happened in this case)”.

What was it?

“Oh I got a particular impression”. |

I am impressed by the reading.

And that made me say that I had observed something besides the mere seeing & speaking.

“Something peculiar happens when I read”. That is I am impressed. |

The words are old acquaintances of mine.

But do I always have

to || towards old

acquaintances the one feeling of old acquaintance. |

The words easily awaken feelings in me.

Odd scratches don't.

I can easier feel at home in well known things than in others. 89 |

Music impressing you

“sad”, “joyful”,

etc.. |

The only adequate way of expressing your impression might be to draw what

you see.

|

“An impression” sounds like something

amorphous. |

“Do you remember having lived yesterday?” |

Can one remember without language.

Can one wish to be somewhere at 5.05 o'clock if one knows no clocks. |

What is the difference between a memory image & an image we deliberately make up.

|

Russell doesn't

really wish to say that two classes are similar if they are

correlated.

He needs a correlation which isn't a grossly material one, which

in fact is the possibility of a material correlation.

And that means that when he says A & B are

1-1

correlated it really means they can be, or it

makes sense to say that they are.

So we are driven to consider cases in which it makes sense & such in which it makes no sense to say that 91 two classes are

1-1

correlated.

What is the condition of their being 1-1 correlatable. |

What in this case is the condition.